An unassuming Kentucky historical marker sits in the strip of grass between a medical office suite and U.S. Route 27. Most people passing by wouldn’t be able to make out any of the rusted words embossed on the state marker, let alone read the entire story.

The intersection of Interstate 471 and Alexandria Pike, where the sign resides, is a somewhat sleepy sight to behold these days. Besides a Liquor Barn and the offices of a digital pharmaceutical provider, there isn’t much you might notice. But just 50 years ago, it was home to one of the hottest nightclubs in the region.

The History of the Club

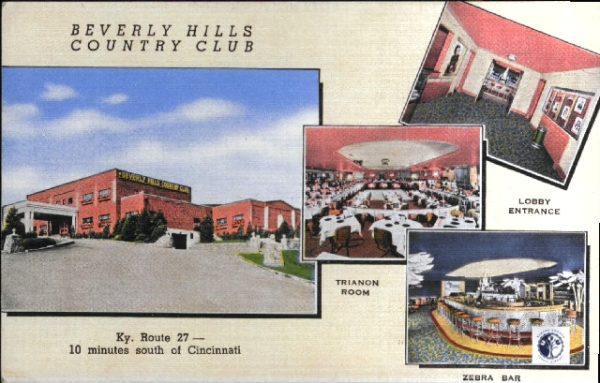

The Beverly Hills Supper Club was more than just a nightclub; it was a cultural hub. Originally opened as the Beverly Hills Country Club in 1935 by local businessman Pete Shmidt, the glamorous club was a hot spot for gambling and live entertainment. The club hosted some of the country’s most famous and influential entertainers. Frank Sinatra, Jerry Lee Lewis, Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons, and a multitude of other legendary performers passed through the esteemed venue.

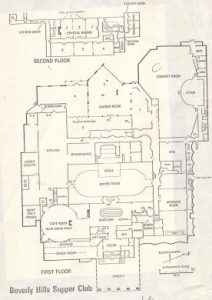

By the 1960s, the club had been purchased by a number of organized crime figures. Newport was a hub of mob activity and organized crime during the “sin city” era from the 1930s to the 1960s. In 1974, the club was sold to Richard Schilling. Between 1970 and 1976, several additional rooms and venues were built onto the existing structure of the club. These editions resulted in a sprawling, non-linear complex that was not the most intuitive to navigate.

May 28, 1977

On May 28, 1977, the Memorial Day Weekend of 1977, the nightclub was bursting at the seams. The official capacity for the building was 1,500, but an estimated 3,000 guests were in attendance that Saturday night. Many of those guests squeezed into the notorious Cabaret Room, the club’s largest event space. An expansive dinner hall with a large stage, the room’s typical maximum capacity was for 600-700 people. That night, around 1,000 people were crowding inside to see singer and actor John Davidson perform.

On the opposite end of the club, in a small event space called the Zebra Room, a wedding reception was wrapping up around 8:30 p.m. Some of the guests had complained of hearing loud explosions beneath the floors and the room being too hot. The wedding party had left early because of their complaints, leaving the Zebra Room empty until 9:00 p.m., when a club employee smelled smoke. She opened the door to the Zebra Room to confirm her suspicion of a fire. The staff alerted the fire department and began utilizing fire extinguishers, but the act of opening the room’s door had allowed enough oxygen inside for the growing fire to flashover quickly and engulf the Zebra Room in flames. Suddenly, the fire extinguishers were not enough to suppress the fire.

The decisive factor in the fire’s volatility was the environment of the club itself. Faulty wiring, no centralized fire alarm or sprinkler system and a confusing layout with too few exits set the club up as a prime location for a tragic event. Another factor at play was the materials used to build the club; flammable wood paneling and shag carpeting were like kindling, spreading the fire extremely quickly.

Because the club had no fire alarm system, the only way for patrons to be alerted to the fire was by word of mouth. By the time those in the Cabaret Room were alerted to the fire by Walter Bailey, a busboy at the club, the fire had practically reached the room.

At 9:05 p.m., firefighters arrived on the scene and began their efforts, but the number of guests and the lack of exits heightened the chaos. Immediately after firefighters arrived on scene, at 9:06

p.m., the Cabaret Room was ordered to evacuate, but smoke and flames had already begun to engulf the venue. The Cabaret Room only had three exits, none of which were properly marked, leading to confusion. Massive crowds shuffled towards the exits, and at 9:10 p.m., the club lights went dark, causing a panic. The large crowd crushed towards the doors, making exiting even more difficult and creating worse bottlenecks: tight congestion points where too many people tried to fit through too small an opening.

By this point, two of the three exits were blocked by fire, and the number of frantic patrons trying to escape had made it impossible for many to get out. The layout of the building only added to the confusion.

At 11:30 p.m., firefighters were ordered out of what remained of the Supper Club shortly before the roof collapsed. They worked to control the blaze, but it took them until Monday, May 30, to extinguish the fire.

The Aftermath

The tragedy didn’t stop when the smoke cleared. In the days following the fire, the nearby Fort Thomas Armory (now Fort Thomas’s Tower Park) was converted into a makeshift morgue for the victims of the fire. The final death toll reached 165, with over 200 more injured, making it the deadliest fire in Kentucky’s history and the third-deadliest

nightclub fire in United States history.

The investigation into the fire revealed heavy negligence. The lack of sprinklers, the absence of a fire alarm and the extreme overcrowding were all contributing factors to the tragedy. The catastrophe led to an overhaul of Kentucky’s fire codes.

The Beverly Hills Supper Club fire also became a landmark case in the legal world. Lead attorney Stan Chesley filed a massive class-action lawsuit on behalf of the victims. In a pioneering legal move, the suit targeted the manufacturers of the aluminum wiring found in the club, arguing it was inherently dangerous. The resulting settlements totaled more than $49 million, fundamentally changing how product liability was handled in American courts and creating the enterprise liability doctrine often used today in similar class action suits.

Today, the hillside where the club once stood is quiet, far from the glitz and glamor of a time long since passed. In 2023, a permanent memorial was dedicated at the foot of the hill, featuring names of the victims and a tribute to the first responders who arrived that night. Two large plaques tell the history of the club and fire, and memorialize what was lost that night.

While that rusty historical marker may lack the glamour of the venue it honors, its value is far greater. It is a stoic reminder of a night that left a deep scar on the region. It’s a far cry from what once was, but it holds a quiet, heavy stillness that speaks for the lives lost and the lessons we are still bound to remember.

Editor’s Note: This story marks the debut of Crawford’s Corner, a new column by Editor-In-Chief Henry Crawford that will go in-depth into the fascinating local history of Northern Kentucky.