DISCLAIMER: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of The Northerner.

As I drove to my summer job one evening last week, I decided to deviate from the classic rock radio station that stays permanently tuned on my car’s radio 24/7. I flipped through several stations, most of which were broadcasting commercial breaks at the time.

One station wasn’t; it was just introducing its next group of songs as I tuned in. “Top 40 hits” was the genre.

Now I’ll admit, I am a fan of all kinds of music. I will listen to practically anything, but current pop hits are undeniably an area where I lack much listening experience. Still, as someone who is always open to new things, I decided to listen in and broaden my horizons to what is topping the charts these days.

As I listened, something stood out to me, not so much in what I heard, but in what I didn’t. Despite all the emotion and high energy in these chart-topping songs, there was a noticeable absence of something that once defined major waves of popular music: politics.

I kept track of a few of the songs I heard:

Sabrina Carpenter – “Man Child”

Kendrick Lamar – “Luther”

Benson Boone – “Sorry I’m Here for Someone Else”

Chappell Roan – “Good Luck, Babe!”

Each one was catchy, extremely polished and emotionally charged. But thematically, they all revolved around the same subject matter: love, heartbreak and personal drama. What I noticed wasn’t that the songs were bad, far from it, but that none of them seemed remotely interested in engaging with the world beyond the individual self. Politics, protest, or cultural commentary? Nowhere to be found.

Songs about love, romance and turmoil have always been a cornerstone of popular music, but while these themes remain strong, politics seems to have been almost entirely removed from the space.

Music has been recognized as a form of political expression for millennia. The Greek philosopher Plato once wrote, “musical innovation is full of danger to the whole state, and ought to be prohibited. When modes of music change, the fundamental laws of the state always change with them.”

Political music is far from a novel concept. Even politics in pop music isn’t a new idea. Here are some examples from the 1960s.

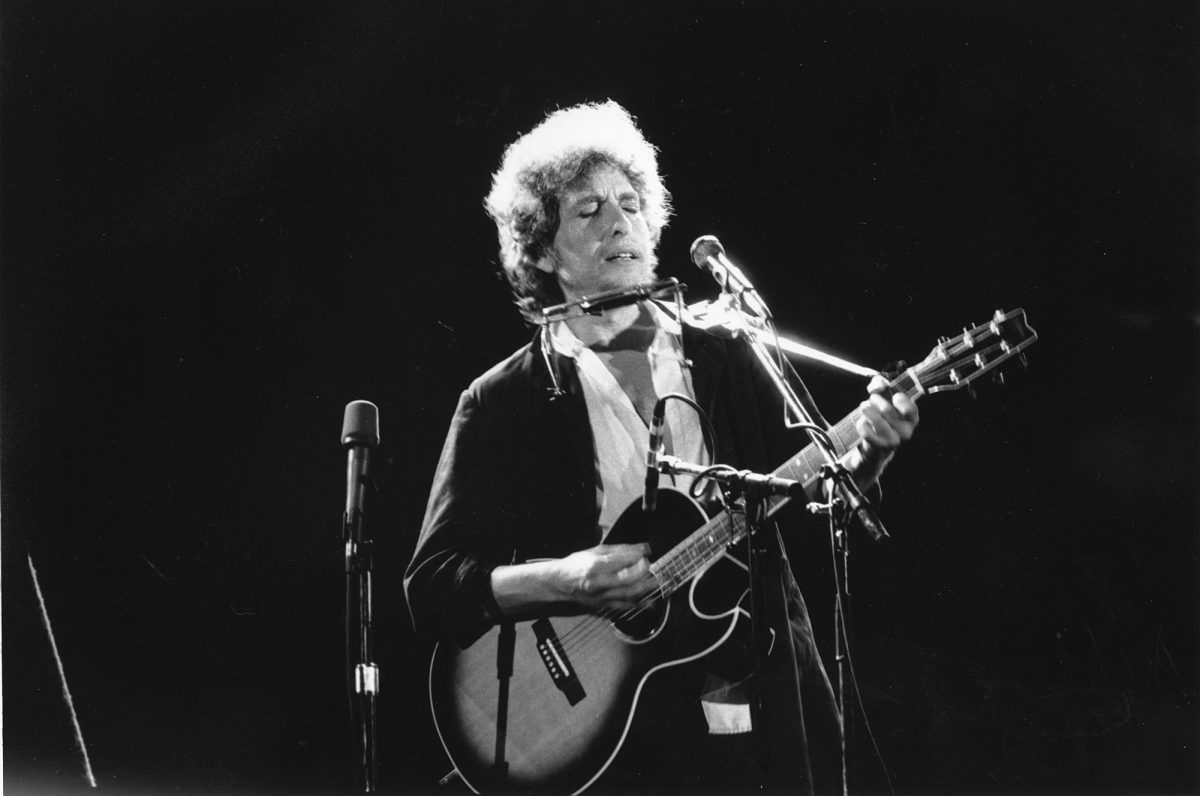

“Fortunate Son” peaked at no. 3 on the Billboard Hot 100 charts. “Respect” by Aretha Franklin reached no.1. “Blowin’ in the Wind” reached no. 2. These are songs that were not only commercial successes but cultural and historical time capsules of the political salience of the era.

My favorite example is Barry McGuire’s 1965 anti-Vietnam War protest song, “Eve of Destruction.” This track not only went to no. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, but did so with some of the most blatant and least masked lyrics of any protest song ever. If you haven’t heard the song, I encourage you to give it a listen and pay attention to each lyric. It’s not only an example of how well music can be used to express political thought, but also how successful that music can be in spreading its message.

To be clear, politics in pop music hasn’t disappeared completely. Many artists, including some mentioned earlier, have written powerful, poignant tracks with deep political meaning.

Kendrick Lamar is possibly the most commercially successful modern example. His 2015 track “Alright” was not only a critical success but became an anthem for protesters against police brutality. The chorus, “We gon’ be alright”, echoed through streets at Black Lives Matter protests, turning his music into a form of political resistance. This one track is just the tip of a massive iceberg of Lamar’s politically charged work.

And yet, “Alright” only reached No. 81 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Obviously, critical success isn’t defined by one chart, but it says something about the current musical landscape that even politically impactful songs often fall short commercially. Meanwhile, less political songs by the same artists tend to dominate the charts.

Take Lamar’s 2024 hit “Not Like Us,” for example. The track permeated every aspect of American culture over the summer and reached number 1 on practically every U.S. chart. While it undeniably references many cultural issues, its central focus is a personal feud with Drake. Despite Lamar being one of the most politically poetic lyricists of our time, even a Pulitzer Prize winner, his biggest hit in years succeeded not because of its political content, but despite its lack of it.

At the end of the day, I am not a music industry insider. I don’t know the ins and outs of what may have caused this large-scale shift in pop music to be almost entirely apolitical. But I do know it hasn’t always been this way.

Imagine the impact if Taylor Swift released this generation’s “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Or if country artists like Morgan Wallen or Luke Combs wrote the next “Folsom Prison Blues.” Or if a rising star like Benson Boone released an anti-war track for the ages.

Maybe my pipe dreams of major pop artists becoming politically active in their music are just that, dreams. After all, none of these people is required to write about anything other than what they see fit.

Despite the title of this article, politics in pop music isn’t completely dead, but it’s on life support. The top artists of today have enormous cultural influence. If even one of them decided to channel that power into music that speaks to the political moment we are currently living through, the ripple effects could be massive. Maybe it’s not an obligation, but it is an opportunity. And right now, it’s being missed.