Former Kentucky Poet Laureate and award-winning author Crystal Wilkinson will visit NKU’s campus on Tuesday for a free, public reading and dialogue in the Eva G. Farris Reading Room at Steely Library.

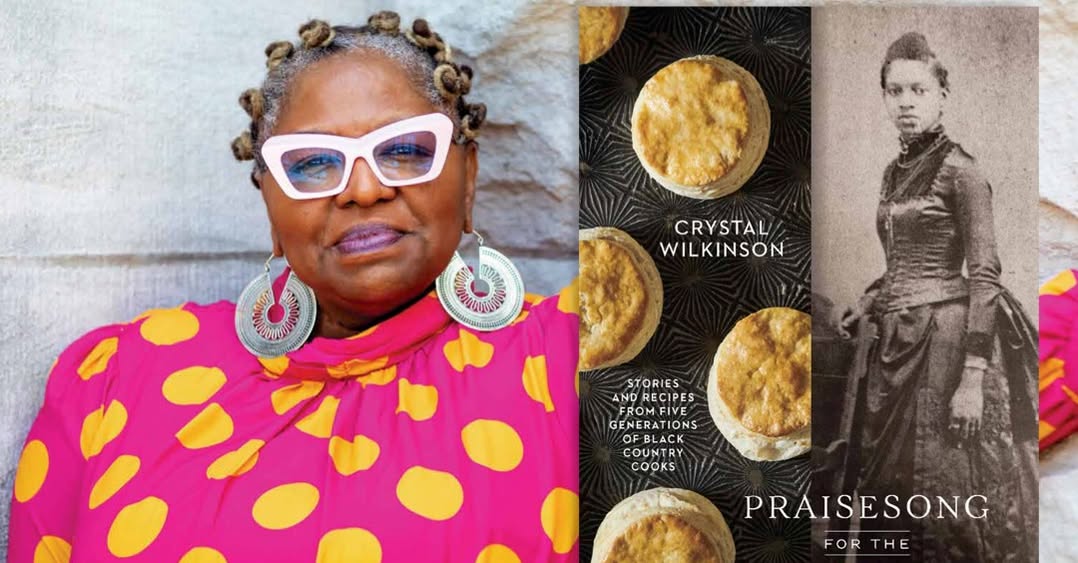

The event, slated to take place at 6:30 p.m., will in part discuss Wilkinson’s newest best-selling book, “Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts,” a culinary memoir that highlights Wilkinson’s connection to her heritage through food and story, and may feature a reading from the novel she’s currently working on, “Heartsick.”

“Everybody has a food story, everybody has someone in their family who either cooks horribly or cooks well, because your kitchen ghosts don’t have to be the fabulous cooks, you can be haunted by someone who never cooked well,” Wilkinson said. “That can also be your inspiration of why you want to cook a particular dish or why a particular meal is memorable. I think that that is universal, food is culture, food is region, so I’ll be talking about that.”

Appointed Poet Laureate of Kentucky in 2021, Wilkinson was the first Black woman to receive the honor. Her work as an author spans poetry, fiction and nonfiction, and her work often draws from her experiences growing up Black and Appalachian.

Wilkinson, alongside peers such as Frank X Walker and Kelly Norman Ellis, makes up part of what is known as the “Affrilachian” community, a term coined by Walker to help contextualize life as a Black person from the Appalachian region.

Wilkinson was born north of Cincinnati in Hamilton County, Ohio, in 1962, but was brought up on her grandparents’ farm in Indian Creek, Kentucky— “the hills,” according to Wilkinson. Because her mother struggled with mental illness, Wilkinson was raised primarily by her grandparents and grew up alongside her first cousins, who “were kind of like my siblings,” Wilkinson said.

“My county was probably then, like, 97% white, so my family was the only Black family I knew, everybody that I knew that was Black, I was related to,” Wilkinson said,

Growing up “really, really shy” in an isolated, rural area led Wilkinson to turn to literature for refuge.

“I didn’t have a lot of friends that weren’t relatives … to read and write was my thing,” Wilkinson said. “My grandmother always said that by the time I got through reading all the books in the house, I started making up my own stories and writing my own books.”

Wilkinson said fiction has “always been my thing.”

“I enjoyed making up stories, writing stories and creating characters that I would try to figure out what kind of people they were and what was going on internally,” she said.

Being shy inspired her work.

I think creating those characters and putting them in situations outside myself was kind of a way for me to express myself,” Wilkinson said.

She also excelled in academics. She was sixteen when she graduated from high school, having skipped a grade. From there, she attended Eastern Kentucky University, graduating in 1985 with a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism.

Wilkinson credits another former Kentucky Poet Laureate, the late Gurney Norman, as a mentor early in her journey as a professional writer. She said he had a way of casually bringing up things that are life-changing.

“He would invite me, as a new writer, to go to the places that he was going—I wasn’t invited to those things, but he would say: ‘Crystal I’m going to pick you up … I’ve got this reading, and I want you to read some of your work with me,’ and I’d go: ‘Are you sure? Me?’ And I thought he was doing it just to do it, but all of that was very intentional,” Wilkinson recalled.

Currently, Wilkinson teaches at the University of Kentucky and is a mentor in her own right.

“Working with graduate students and first-year students who are making decisions about whether writing is something that they’re interested in is wonderful,” Wilkson said.

“Teaching and community teaching, it’s always been a big part of my passion … Gurney was really important in my writing career, and I hope that I’m able to do some of the same for the young writers that I work with,” Wilkinson said.

Though she’s taught at numerous collegiate institutions over the years, Wilkinson said teaching in community spaces like the Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning in Lexington, Kentucky, was equally valuable.

“[At the Carnegie Center] I might have a high-school student, a seasoned writer and a senior citizen all in the same circle working on their short stories, or working on their poems, so that is fulfilling and inspirational for me too as a writer,” Wilkinson said, “because I feel like those communities don’t cross as much as they could, or as much as they should.”

As for her writing process, Wilkinson said that she’s generally “still pretty old-school.”

“There is still nothing like pen and paper for me,” she said.

Her routine begins before most people wake up.

“I have always been a writer who writes best at 4 a.m., I know that’s not for everyone,” Wilkinson said. “For me, that’s always been an important part of my process…I find that that’s when artists are closer to their dream states, and are closer to having a fresh, creative mind.”

Wilkinson said she believes in tending to her art first.

“If you’re really intentional about it, I think that getting up before the rest of the world wakes up and making art is important and fulfilling,” she said.

Wilkinson also mentioned that she’s “not very linear” with her writing.

“A lot of writers—whether they’re writing poems or essays, short stories or books—will start on what they think is the beginning,but that’s not a part of my process,” Wilkinson said. “I will begin at the various points in the project that interest me and then go back and build bridges from one scene to another, or one stanza to another, or one line to another—sort of a ‘mosaic’ approach.”

Another aspect of Wilkinson’s writing that makes her unique, according to Dr. Kristine Yohe, an English professor at NKU, expert in African American literature and a personal friend of Wilkinson, is her unique perspective and vulnerability.

“I think she’s very open and honest. She writes about a black rural experience, and that’s unusual,” Yohe said.

Wilkinson has a unique way of telling a story, Yohe said.

“She’s got a very distinctive voice in the way she writes about authenticity, and I think it’s very distinctive in how open and vulnerable she’s willing to be, but how she also shows the multiplicity of Blackness,” Yohe said. “[Wilkinson] talks about rural Blackness. She has a poem called ‘O Tobacco’ about her grandfather being a tobacco farmer—that’s not a perspective I’ve ever seen anywhere else from a Black woman.”

Yohe, who plans on attending the event on Tuesday, said she hopes that students come and “recognize the power of creative writing, the power of the written word, and how it can represent a multitude of people.”

“She really lives her art, she’s open and honest and willing to be vulnerable and I think that can help students of all sorts,” Yohe said. “With writers, if they share their vulnerability, we can connect to them more in some way, because we all bring our own lives to what we read, so I just find her authenticity and her openness really wonderful.”

Yohe said all the “Affrilachian” poets, but Wilkinson particularly, are willing to tell the truth and defy stereotypes.

“So, I hope the students see that Kentucky writers come in all identities, they come in all races and ages, they represent a range of things, because I think that helps with anybody who identifies with an aspect of the different things she presents, she helps them not feel alone,” Yohe said.

On her ability to write so openly, Wilkinson said, “I think that a writer has to write what haunts them.”

“Heartsick,” the novel Wilkinson is currently writing, draws largely from Wilkinson’s relationship with her mom.

“Because of my experience with my mother, a thread of truth in my writing has always been mental illness…and because of my own personal experience with my mother, it’s one thing that haunts me.”

Wilkinson said that, through her body of work as a whole, she hopes she can “put Kentuckians on the minds of the rest of America and internationally.”

“I want people to think about who a Kentuckian is from any time period, I’m always wanting to write about the state, the region, whose Appalachian, whose Black and Appalachian, so in many ways in doing that I am constantly paying homage to my own ancestry, even if it’s fictionalized,” Wilkinson said. “I am wanting to hold up the way that I grew up and the people—real or imagined—up to the light in some way. To say, this is Kentucky too, this is Appalachia too, look at it from this angle.”