When President Donald Trump signed an executive order withdrawing the U.S. from the Paris Climate Agreement, it came with a lot of disappointment and loss of hope.

“It’s disappointing for everyday people. It’s sad for the world, for species, for habitats and for folks that live in the middle of downtown Cincinnati that can’t afford an air conditioner. I think it’s a bummer,” said Dr. Kristy Hopfensperger, an environmental scientist and a professor at NKU.

With that being one of many executive orders Trump signed off on his first day of office, it was one people expected to happen. In his first term as the 45th president, Trump pulled us out of the Paris Climate Agreement that Barack Obama first put us in, on September 3, 2016.

Exiting the agreement put the U.S. as one of four countries not to take part; the other three countries are Iran, Libya and Yemen.

For some context on how big this is for the nation and the world, we are the world’s second biggest emitter of planet-heating pollution right behind China, according to the World Resources Institute.

What is the Paris Climate Agreement and how does it work?

According to the United Nations Climate Change webpage, The Paris Agreement is a “legally binding international treaty on climate change.”

The Agreement requires “economic and social transformation, based on the best available science.” It works on a five-year cycle, increasing ambitions on climate change every five years, carried out by each county. From the year 2020, countries have to submit their national climate plans, better known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Each successful NDC a country has to submit is meant to reflect an increasingly higher degree of ambition compared to the previous plan.

Overall, the goal is simple: To slow down climate change. But the path to that goal poses some difficulties, especially since not everyone is on board.

Expert Views on the Paris Climate Agreement

Dr. Rhonda Davis, the director of interdisciplinary studies and an environmental studies scholar at NKU, said we’ve gotten to a point where we have to act now, and with one country doing it and the rest not, it’s not going to work.

She believes the Paris Climate agreement hasn’t done as much as it could have.

“I think most importantly, it sheds light that this is a serious global problem, and that we have industrialized nations involved in helping developing nations who are disproportionately affected by climate change. So I think as a structure, it’s good for that. It helps raise money for developing nations who are really struggling,” Davis said.

Dr. Thomas Bowers, associate professor in NKU’s Department of English and the author of “Environmentalism and Contemporary Heterotopia: Novel Encounters with Waste,” has pretty similar views to Davis.

Bowers believes the Paris Climate Agreement has had a minimal effect on climate change.

“It’s hard to do it globally. The mindset seems that the emphasis is on technological fixes and how can technology help solve climate change without disrupting the economic ambitions of all the countries, and then the development issues. So you have all of these issues trying to come together,” he said.

He looks at the Paris Climate Agreement through a technological mindset and sees a lot of issues arising globally.

“How do we address the climate change without completely disrupting efforts to address economic problems throughout the globe as well… I think that creates some problems with trying to balance those. So I think it does a little,” he said.

Bower wants people to become engaged in the process of making climate agreements. He said it is a global process, so everyone should have a stake in that.

Davis studied climate change for most of her life, reading book after book. The thing she wants to see is better accountability with climate agreements.

She’s seen a lot throughout the last couple of years when countries and companies pull out of their commitments.

“I would like us [the U.S.] to acknowledge the reality that climate change is accelerating and it is human-caused. The political ideology of removing ourselves from the Paris Climate Agreement is just hurting us,” Davis said.

Davis said it is not good for industries, accountability and planetary health.

Hopfensperger also wants to see accountability through holding nations to their word.

“That’s kind of in the history of these COP meetings (Conference of the Parties) that everyone gets together and says we’re going to do these amazing things, then the goals are never reached. It’s important to set goals, to have something to work towards, but there needs to be follow-through,” Hopfensperger said.

She said there are no repercussions.

Administration Views

In a statement to the press, Trump argued that the Paris Climate Accord hurts the American people.

“The Paris Climate Accord is simply the latest example of Washington entering into an agreement that disadvantages the United States to the exclusive benefit of other countries, leaving American workers — who I love — and taxpayers to absorb the cost in terms of lost jobs, lower wages, shuttered factories, and vastly diminished economic production,” Trump said.

He said he is willing to work with other global Democratic leaders to either negotiate a way back into the Paris agreement under terms that are fair for the United States and its workers, or negotiate a new deal that protects the U.S. and taxpayers.

“So if the obstructionists want to get together with me, let’s make them non-obstructionists. We will all sit down, and we will get back into the deal. And we’ll make it good, and we won’t be closing up our factories, and we won’t be losing our jobs. And we’ll sit down with the Democrats and all of the people that represent either the Paris Accord or something that we can do that’s much better than the Paris Accord. And I think the people of our country will be thrilled, and I think then the people of the world will be thrilled. But until we do that, we’re out of the agreement,” Trump said.

Lee Zeldin, Trump’s pick to lead the U.S. The Environmental Protection Agency acknowledges climate change, unlike his fellow party members, including Trump. But he agrees with them that pulling out of the climate agreement is good.

But NKU professors are not fond of Trump’s decision.

Bowers, Davis and Hopfensperger all believe that Trump pulling us out of the Paris Climate Agreement was a bad thing for people in the U.S.

“I don’t think it’s good because the public will see the government doesn’t care about it. It makes it harder to engage the public. The problem isn’t going to go away magically, from a leadership standpoint, it generates a different public perception about climate change,” Bowers said.

Davis said, “I think that it’s purely ideological. I don’t think there’s any benefit. I think he’s doing it because he can do it, and it’s part of his narrative of isolationism, America first…it’s this sort of story that he and his followers and people he’s put in power. It’s a story they tell themselves that we’re being taken advantage of. It’s that typical victim mentality, America is being taken advantage of…. Millions of people will die from this, it’s really scary.”

Effects of Climate Change

We often think about human-induced climate change as something that will happen in the future, but it is happening now. One main issue is the extreme weather.

Bowers, Davis and Hopfensperger all said Kentucky’s weather will stay on the path of being erratic and extreme.

Bowers talked about the unpredictability of Kentucky’s weather.

“I mean, we just had a cold January, but then two days later, after that cold snap, we had a record heat. Is this summer? It’s going to wind up being dry like last summer, there’s going to be too much precipitation…I don’t think it’s [just] the unpredictability. I think it’s the extremes and that unpredictability,” Bowers said.

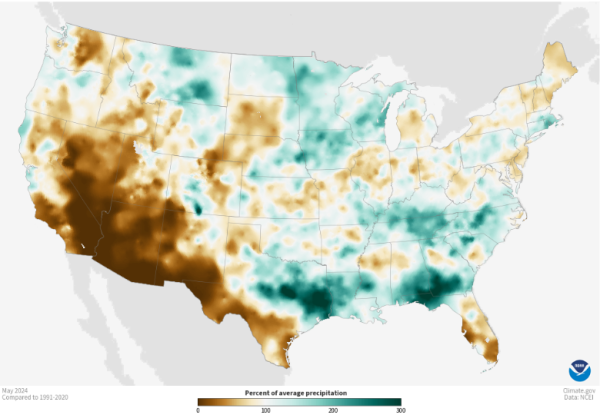

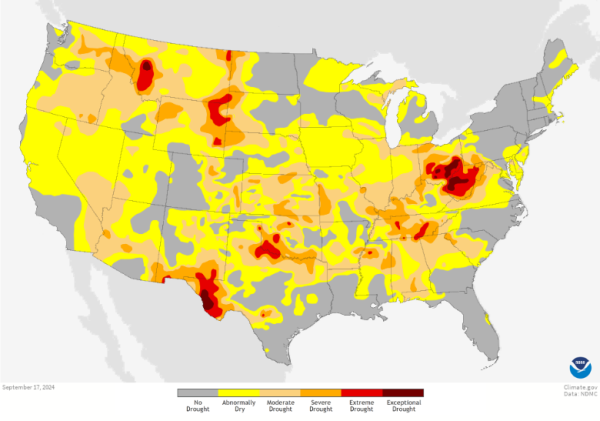

Davis said, “What we’re seeing as a result of climate change right now, of course erratic weather, more rain episodes where we have heavier rain, so we can still have drought, but have heavy rain episodes, we’re seeing higher temperatures, more humidity, which is difficult for agriculture, people and animals. It’s difficult for everything.”

The environmental studies scholar went on to say that Kentucky is not immune to climate change. Even though we are not in a coastal area where people are seeing dramatic impacts, it doesn’t mean that we’re not seeing the effects ourselves.

Hopfensperger points to the issue of droughts.

“We will continue to get warmer and we will have a funny things happening in our region with precipitation. So we are supposed to get heavier rain. So when it rains, the rain is going to come down really fast, that can actually lead to drought. So for farmers, we might expect drier soils, but also more flooding, because when that rain comes down really fast, it doesn’t have time to slowly soak into the soil for the plant roots. When it comes down really fast, it runs off the land into our streams. So our streams and rivers may flood more, but our plants also might be drier because the rain is not soaking into the ground,” Hopfensperger said.

Hopfensperger also went into how climate change has affected flora and fauna.

“The species and the habitats that are most impacted are those that cannot kind of shift across land. So I think of like the tops of mountains, all the species there, plants and animals, are acclimated to that temperature and moisture amount, and they can’t move up because the mountain ends. So they are most at risk. Same with, like the Arctic, a lot of people talk about the polar bears. You can’t go north if you’re at the North Pole, so they’re most at risk. The other ecosystem and habitat, and species that is most at risk is the coral reefs,” Hopfensperger said.

Diseases and health are also at the forefront of climate change. Hopfensperger brought up different species of mosquitoes and ticks that carry diseases; these species’ ranges will shift northward.

Climate change makes it extremely difficult for animals to adapt. That goes to the topic of natural selection, where a species can either adapt, move or go extinct. Not every species moves at the same rate, so a lot of animals die from the heat.

How can a regular person help combat climate change?

Bowers believes there are subtle ways people can help combat climate change, and that’s through self-made goods.

“Plant a garden. If you like to sew or knit, make some of your own clothes, socks, those small little things, just and from the consumption kind of standpoint is where I come from,” he said.

Bowers thinks about the packaging, the product, and the manufacturing of something he wants to buy and how that can correlate to the change of the climate.

He wants to limit his consumption, so he goes thrift shopping and to second-hand marketplaces. It’s nothing drastic, but if people can give up something that plays a role in helping combat climate change, why not?

“Small steps to thinking about our consumption habits, I think it’s a start,” Bowers said.

Davis thinks a simple way people can slowly start to combat climate change is by not driving so much.

“Our reliance on fossil fuels is horrible. Now that is easy to say that, but less easy to do because we don’t have public transportation infrastructure like we should… what are you supposed to do? But things I think you can do is carpool or take less trips, don’t just drive around for the sake of driving around and don’t leave the house several times a day,” Davis said.

She went on to say that those cumulative impacts make a huge difference. She urges people not to just think “let’s recycle and it’s all going to go away,” she wants people to realize that this problem is multifaceted and a complicated thing.

Hopfensperger thinks the best action a person can take is through policy, voting and democracy.

“So if we pay attention to local policies that are happening, what’s happening locally with our transportation, what’s happening locally with our use of water, things like that. Or does our state support incentives for doing renewable energy for your vehicles or for your home?” She said

Hopfensperger believes the decisions people make at the polls are where the most impact comes from.

“Supporting the people that make these decisions through our vote is where impact can really happen, and there’s going to be greater impact happening if we’re knowledgeable of what’s happening in our area. How we can use our sway as a resident and a voter, that’s going to be more impactful getting those people into policy-making positions than just recycling your pop can,” Hopfensperger said.

Conclusion

Climate change will be the spark for many problems across the world for many years to come, whether that’s rising sea levels, extreme weather, habitat loss and climate refugees.

Even though Trump withdrew the United States from the Paris Climate Agreement, it won’t keep Bowers, Davis and Hopfensperger from spreading the word that climate change is happening and it is happening now.

They will keep fighting for the planet’s health, showing what it means to put the world first.

Bowers said, “I go back to the late 1960s and early 1970s, and I know it was a different time, but it always sticks out in my mind. With the Apollo missions to the moon and the pictures that they showed and brought back… That picture of the Earth coming up over the moon really served at the time to galvanize people to help the environmental movement; all of us are on this blue ball together. In this contemporary world, we don’t have that kind of metaphor or symbol to help us recognize that.”