This story was written in partnership with LINK nky, Northern Kentucky University’s Advanced News Media Workshop class and The Northerner for this series on the changing face of Northern Kentucky.

Read the other stories in the series here:

- The face of Northern Kentucky: ‘It’s starting to look different’ by LINK nky’s Haley Parnell

- Congolese native’s journey inspires hope for others by The Northerner’s Elita St. Clair

- Five international markets share a slice of home by The Northerner’s Elita St. Clair (with video)

- Tiburcio Lince brings ‘alegría’ to Latino Student Initiatives at NKU by The Northerner’s Shae Meade

Decades ago, in a quiet German village, a pastry chef opened his bakery at dawn. He carefully prepared the dough using sacred baking traditions gathered from across Europe.

Sixty years later, his grandson continues the same story, opening the bakery at dawn just as his grandfather did all those years ago.

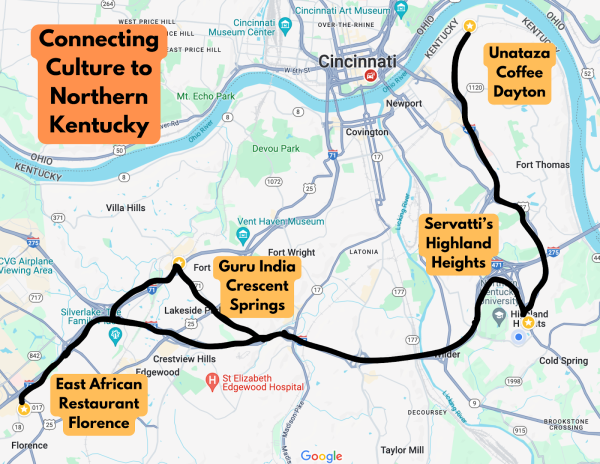

Instead of Germany, though, the bakery is in Highland Heights. The Servatii’s Northern Kentucky location is one of several immigrant-founded restaurants on this side of the Ohio River that help connect the area to cultures from around the world.

Servatii’s, Highland Heights (one of 15 Greater Cincinnati locations)

(German bakery)

Distance from Servatii’s, Highland Heights, to Münster, Germany: 4,240 miles

Proudly dubbed the “no fakery bakery,” Servatii’s prides itself on honest products made with the same techniques that started in Germany. Café Servatii was founded by George Gottenbusch in Münster, Germany. His son, Wilhelm, brought the Servatii name to the Tri-State.

Georg’s grandson, 52-year-old Greg Gottenbusch, is now the owner of the Highland Heights Servatii’s, dedicated to continuing his family’s long-standing traditions. His earliest memories with his grandfather involve long days of cookie-packing in the flour-dusted bakery.

“As kids, me and my sister would sit around the bakery after school and pack up gingerbread houses and cookies,” Greg Gottenbusch said. “The smells were just incredible. The bakery was our playground. It takes me back to being a kid again.”

Gottenbusch studied pastry-making at Germany’s most recognized pastry school, emphasizing the importance of honoring tradition. After high school, he visited Germany to educate himself on pastry and walk in the footsteps of the generations of bakers before him.

“It was so special to me, to stand in the hallways where my grandfather made his cakes for the first time,” Gottenbusch said. “It was a bit intimidating at first, but then I started to love it. I want to continue his legacy for as long as possible.”

When Gottenbusch’s father moved to the U.S. to continue the family business, the journey was far from easy.

“When my dad came here, he had nothing,” Gottenbusch said. “He was definitely treated differently for being German, but he didn’t let that stop him.”

Servatii’s most popular pastries are their carrot cakes and pretzels. From a simple, village bakery to a regional household name, Servatii’s has earned its place as a symbol of immigrant resilience, tradition and success.

East African Restaurant, Florence

(Somali cuisine)

Distance from East African Restaurant, Florence, to Mogadishu, Somalia: 8,179 miles

In the heart of Florence, the aroma of Somali spices may whet your appetite. Although it was founded in Northern Kentucky in 2019, East African Restaurant’s cultural roots are grounded in the heart of Mogadishu, Somalia.

Mahmoud Dhudhi, 40, grew up on a large farm with his brothers and sisters. They grew everything from watermelon and sesame to onion and papaya. Tea with milk, mouth-watering chicken suqaar and sambusas are just a few of the tastes that shaped Dhudhi’s cultural identity.

“For me and my family, we didn’t go hungry. That was important for us,” Dhudhi said. “I never want someone to be hungry. Community and family is a huge part of why I love connecting with people.”

He came to the United States for a chance at a new life and the opportunity to share his identity and culture with Northern Kentucky. He arrived in Columbus, Ohio in late 2005, aspiring one day to open a restaurant with his brother, Zaq.

Even as the African community expanded, finding the opportunity to live his dreams as a restaurant owner proved challenging. He felt the need for more representation in Northern Kentucky, starting with his deep love and appreciation for food.

“Somali food is not popular here, but when people come and try it they love it,” Dhudhi said. “It’s exciting to add a new thing to the neighborhood and give people more options.”

During his time in the U.S., Dhudhi said he strategized about how to bring the vibrancy of his culture to life here. Cultural barriers, unfamiliar locations and the quest for a perfect location required patience and resilience, he said.

In 2019 those dreams became a reality, and he opened the first East African restaurant in Northern Kentucky. East African Restaurant mainly caters to the Somali palate, but it also serves as a cultural hub for other neighboring communities in Dhudhi’s home.

“I wanted to create a restaurant that honors my culture and others,” Dhudhi said. “Our foods are similar, but we all have distinct ways of preparing food. It makes sense to open a restaurant that benefits more than one community.”

For Dhudhi, his purpose highlights the diverse influences that shape Somali cuisine and encourages intercultural exchange. His restaurant serves as a platform where different culinary traditions can be appreciated; it is also a testament to his resilience.

Unataza Coffee, Dayton

(Honduran Coffee)

Distance from Unataza, Dayton, to Tegucigalpa, Honduras: 2,942 miles

Nestled in the quaint riverside town of Dayton, a Honduran coffee shop awakens locals with the smell of freshly ground coffee and subtle sweetness of Horchata. Ale Flores, 37, said she aims to weave her story into the heart of Northern Kentucky.

Growing up in the lush landscape of Tegucigalpa, Honduras, with her brother, her earliest memories of coffee were experienced with her grandparents.

“Every day after school, my grandparents would bring us home, and we’d enjoy a cup of cafe con leche,” Flores said. “Coffee has always been my identity.”

Flores left Honduras at age 23 with a tourist visa. She eventually earned an MBA from the University of the Incarnate Word, a private, Catholic university in San Antonio, Texas. After graduating, she wanted to open her own business and bring the real taste of Honduras to the U.S.

Her reflections on her hometown’s rich coffee culture set the tone for her mission in Kentucky.

“Honduras is a coffee country,” she said. “You’d sometimes see three or four coffee shops on the same street. Even our gas stations have good espresso machines.”

Making the transition to U.S. life as an adult presented a set of obstacles that went beyond the challenge of opening a new business. Adapting to the changes, Flores weighed in on the everyday differences she experienced once she moved here.

“It was an accumulation of a bunch of smaller things that were challenging,” Flores said. “As an immigrant, driving was much different. And you can’t purchase medicines the same way when you have a visa versus when you’re a citizen.”

Additionally, there were no Honduran coffee shops in Northern Kentucky when she moved here.

The menu at Unataza, Flores said, is a reflection of the rich tapestry of traditions that make up the soul of Honduras. The Tacoma Taquito, a flour tortilla with scrambled egg and grilled peppers and onions, is a fan favorite that satisfies all breakfast cravings. The cafe integrates traditional Latin flavor with a local twist, appealing to a broad audience.

Despite hurdles, Flores envisioned Unataza to be not just a coffee shop, but a central hub for Latin American celebration. The shop provides free Spanish classes every Wednesday, and it showcases local Latin American artistry and small business on their walls.

Caroline Storer, a barista at Unataza, echoes the sentiment of community fostered within the cafe.

“The community comes first,” Storer said. “When you walk in the door we want to make sure you feel connected to the space and the culture. There’s no difference between the person making coffee or washing dishes. We’re all a team.”

This culinary approach to dining illustrates the true meaning of community, inclusion and family. Whether you’re looking for a decadent blend of coffee or a quick bite to eat, Unataza is a crafted getaway to Honduran hospitality.

Guru India, Crescent Springs

Distance from Guru India, Crescent Springs, to Punjab, India: 7,413 miles

Rooted in tradition yet adapting to the tastes of diverse clientele, Guru India has become a key player in the local Indian restaurant scene. Founded by Sonia and Evan, the couple’s mission is to bring the savory tastes of Punjab, India, to the local community.

The family restaurant story started in the early 1980s, when they immigrated to the United States. Evan’s family honored authentic methods of cooking by receiving the community’s blessing. The couple’s son explains the family’s deep love for honoring their roots.

“It was very important to make food for other Indian immigrants,” he said. “We got the approval from them, and then we knew it was good. Then it fell into a larger audience.”

Chicken pakora, tikka masala and samosas are just some of the classic dishes you’ll find in their bustling kitchen. These dishes embody the scents and culinary richness that the family is eager to preserve.

Creating a menu that honors traditional methods while catering to local tastes requires a delicate balance. “Some days we add more spices or cream, depending on tastes,” Evan said. “We realized there’s a demand for vegan options, so we adjust to meet those needs.”

The journey of an immigrant family to the United States is often marked by challenges and a pressing need to thrive in an unfamiliar space. The family not only pioneered the Indian restaurant movement in Northern Kentucky, it founded one of the oldest Indian restaurants in Cincinnati: Ambar India.

When asked about the significance of his culture, the son smiled and offered his thoughts on immigrant resilience.

“Having hope that it’ll work out is forced upon you,” Evan said. “You have to have hope and resilience as immigrants. It’s the key that drives you forward.”