Against the backdrop of buzzy debates over the societal implications of generative artificial intelligence, an NKU professor and his class have harnessed image-generating AI to resurrect historic scenes in a hub of history once on the brink of fading.

Nicholas Caporusso, a computer science professor who researches human interactions with computer technology, taught a course in the Honors College last spring with the goal of applying generative AI, specifically image-creating AI, in a community context. The class partnered with Southgate Street School, a historic school in Newport that served Black students during the era of segregated education, and used the AI image generator Midjourney to tell the school’s gripping story.

After conducting extensive research on the school, the class constructed a narrative of the school’s rich past. First-person accounts from alumni Robert Ingguls and the late Patricia Headen recalling their experiences attending the school parlayed with information gathered from other written sources became the foundation for recreating the school’s past.

These AI-generated images were compiled into a book titled “The Legacy of Southgate Street School” and now offer a window that crystallizes the surviving stories. The book is available on Amazon and Roebling Books & Coffee locations in Northern Kentucky. The proceeds from book sales will be donated to Southgate Street School’s museum, according to Caporusso.

A home of history

Southgate Street School opened in 1873 and closed in 1955 after the Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education found the tenet of separate but equal to be inherently unequal. While the landmark decision patched a major fault in the education system, the closure of Southgate threatened to mark the end of a focal point of local Black history.

The building fell into the hands of Frank “Screw” Andrews, who used the space for his bootleg liquor enterprise. He eventually sold the building to the Masonic Order as an act of reparation to the Black community after facing accusations that he killed Melvin “Numbers King” Clark, a local Black kingpin.

Two key players, Southgate Street School alumni Ingguls and Headen, refused to let the building’s past identity wither with time. Both were affiliated with local Masonic appendant bodies and became ad hoc custodians of the building after the sale. Their will to preserve the building has allowed the school’s legacy to endure, explained Caporusso.

Caporusso and his class have joined the effort to keep the school’s legacy alive with their research and AI-art foray. Newport’s Historic Preservation Officer Scott Clark and Museum Director Daylin Garland helped the students access the school and its wealth of history, setting the project in motion after the students were moved by the school’s resilient story, said Caporusso.

“The legacy of the school, which has been closed for over 70 years now, was basically vanishing. The building is pretty nondescript. If you walk next to it, you wouldn’t even realize what was there, and so we wanted to really give more visibility to the school and its importance,” said Caporusso.

A journey between two covers

Flipping through the book, readers find a concise overview of the school’s history and impact on the community. But the true meat of the book is in the words—and the images they inspired—from Ingguls and Headen.

Biographies of the staunch advocates and quotes about their lived experiences are interspersed with images that revive the past scenes of an ordinary day at the school. In audio recordings, some of which were acquired through interviews with the living Ingguls and others that recorded Headen’s memories before her death in 2015, images of their teachers, classmates, learning materials, lunch times and more were captured.

Those memories are now embedded in images ranging from painterly to cartoonish, mimicking candid photographs, portraits and conceptual interpretations of the school’s essence.

“Considering that it was during segregation and there can be a lot of tension around this topic, it was really inspiring and encouraging to hear so many amazing stories,” said Maddy Del Rio, a student involved in the project, of speaking to people with knowledge of the school’s past.

The creative process

The class negotiated challenges with the unpredictable tendencies of AI and the legal and ethical questions surrounding the burgeoning tool.

Generative AI is becoming increasingly sophisticated as each day passes, but learning to work with it was an inflection point for the Honors College students, who study a diverse batch of academic disciplines.

“It was just hours and hours and hours of working with the AI and trying to figure out how to create prompts that get good images,” said Del Rio, who studies secondary English education. “It’s not as easy as it sounds where you just say, ‘Create this image,’ and it gives you exactly what you had in mind.”

Many of the images Midjourney spat out required considerable fine-tuning to give the scenes proper diligence. The class refined their prompts—inputs given to the AI that tell it what to produce—to elicit the appropriate time period or physical traits of the people being portrayed, said Caporusso.

“Sometimes the algorithm would spit out the image of people with 10 fingers on one hand, so they had to really redesign the images to get something viable out of the algorithm,” explained the professor.

Generative AI is trained on enormous datasets and perceives patterns in the depth of information to generate products based on their understanding of the script it’s provided. AI sharpens its algorithm in a process called machine learning with each generated product and user feedback.

Generative AI has a tendency to shoot out products that misinterpret what the user is looking for because of the vast data it’s trained on. A recurring issue the class ran into was receiving images of multi-racial classrooms rather than the homogenous Black classrooms that were the school’s reality, so Caporusso’s class continually reminded the machine of the parameters of their project.

Debates about the ethics of using human-created writing and images to train AI models have mired discourse about how to use the new tools responsibly. In July, some of the industry’s leading companies entered a voluntary agreement with the White House to implement oversight and guardrails aimed at buffering social and security risks that continuing development poses.

Caporusso gave lessons about the ethics of using generative technologies and encouraged the class members to form their own viewpoint on the matter. “We had kind of a class debate on whether we thought AI generated artwork should be able to compete in art shows with art work that’s created by human hands,” said Del Rio. “Not everybody was in agreement.”

Caporusso said that a common concern surrounding image-generating AI is that the machine simply collages pre-existing work into something new, undermining the creative autonomy of artists.

“That concern’s still out there in the community, because many people still have limited knowledge of what generative AI is. And in that case, the main point is that the generative AI algorithm learns from images that it’s fed with. So it’s like having a human able to visit all the museums in the world at the same time and learning all the styles from all the artists,” said Caporusso.

With the principles of responsible use and accuracy framing the process, generative AI enabled the class’s creativity to shine through a visual medium that may not have been possible with the student’s inherent faculties. “I think it’s a fun way to experiment and create artwork for people who can’t maybe use their hands or somebody like me who’s just—I’m not going to be able to paint something that will be worthy to be in a book like this,” said Del Rio.

Library exhibit

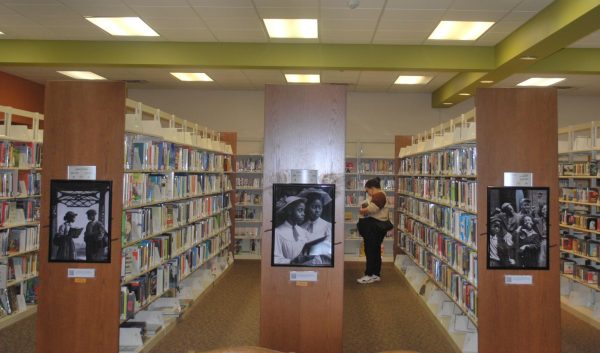

On Wednesday evening at the Campbell County Public Library, the project culminated with an exhibit opening where Caporusso and Del Rio discussed and displayed the class’s work. The exhibit runs until the end of November.

Framed prints of the images found in the book “The Legacy of Southgate Street School” hang on the ends of bookshelves and pillars inside the library. Between the book and the exhibit, South Gate Street School’s story is proving alive and well despite a tumultuous past.

“I think using cutting or new technology to tell an old story is a great way to interest a broader market of people in what you have to say,” said Scott Clark, Newport’s historic preservation officer. “Any way you can tell that story in a way which interests people, I think it’s important to do.”