KRT Campus

KRT Campus KRT Campus

KRT Campus

BANDA ACEH, Indonesia – Relief workers are finding fewer children in camps for tsunami refugees than they’d hoped and fear that children make up an even greater percentage of the dead than was estimated earlier.

“You just don’t see the little kids in the camps: babies, infants and toddlers,” said Christine Knudsen, a senior officer for Save the Children, a nonprofit worldwide advocacy and relief group. “Let’s hope we’re wrong. But that’s the trend right now.”

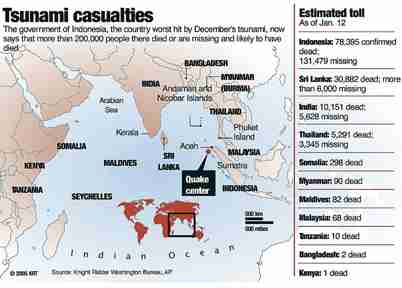

Hard numbers are difficult to come by. Relief workers originally estimated that children made up 3 of every 10 people killed when an earthquake triggered a tsunami that swept the coasts of 12 countries Dec. 26.

But as relief workers canvass camps in Indonesia – the hardest-hit country – to tally the number of children, they’re beginning to reassess their first estimates.

“In all the camps, the number of children is low,” said Frederic Sizaret, a child-protection officer with the United Nations Children’s Fund, better know as UNICEF.

Relief workers hope for a more accurate picture of the child death toll later this month, when schools reopen and they can compare this year’s enrollment with last year’s.

Anecdotal evidence and other early signs lead them to think that children – especially very young ones – couldn’t escape the battering pressure of the tsunami.

“Only the strongest survived in this disaster,” Sizaret said.

Experts originally calculated that children comprised about 30 percent of victims because that’s their relative proportion in the general population, Knudsen said. When relief officials first arrived in Indonesia, they thought they’d find thousands of children either orphaned or missing one of their parents, and many lost children being cared for by other adults.

So far, however, UNICEF and other agencies that are working with minors have found only 400 cases of “separated” children, a term for anyone younger than 18 who’s separated from both parents or from customary caregivers, Sizaret said.

“The number of separated and unaccompanied children is not as high as we feared,” said Shantha Bloemen, a spokeswoman for UNICEF.

“One speculation is that it is because so many children were killed.”

Workers in Aceh province have collected 84,637 bodies so far, with as many as 132,000 more people missing, most of whom, three weeks after the tsunami, aren’t expected to be found alive. Officials haven’t said how many of those are children.

Banda Aceh, the capital of Aceh and ground zero in tsunami-lashed northern Sumatra, is plastered with posters of missing children. A local newspaper, Serambi Indonesia, publishes a page and a half of advertisements daily for missing people, almost all of them children.

“Yoga, Where are you, my son?” lamented a poster with three bright pictures of a smiling lad, stuck to a pillar plastered with other posters outside a Red Cross disaster center. It described a 7-year-old boy, Muhammad Rizka Yoga, with an unusual birthmark on his neck.

“A lot of the people missing are most presumably dead. But in a situation like this you try to do everything you can,” Red Cross spokesman Bernt Apeland said.

The counterparts to the “missing” posters are just inside the central hallway of the center. There, on a bulletin board, are the “I am Alive” lists. Compiled by the International Committee of the Red Cross, they contain more than 400 names of children and adults who want to advertise that they survived the tsunami.

Last week, the lists paid off when a man came in and identified a 9-year-old boy, Maimun, as his nephew. The boy was reunited with his 18-year-old brother, Apeland said.

While reuniting children with relatives is a goal of several relief groups, so is helping children overcome the trauma of losing family, home and friends.

At a small mosque in the outlying city district of Lamgugob, Save the Children counselors offer paper, crayons and building blocks to create what they call a “safe play area.” The area resounds with the boisterous shouts of some 70 kids.

Counselors watch closely to see which kids may be particularly withdrawn.

“One of the most important things in a disaster situation after (children) go through a traumatic experience is for them to come into a normal routine,” said Elisabeth Bakke, a Swedish expert from Save the Children. She added that it was vital for children to play and to return to school as quickly as possible.