KRT

KRTWASHINGTON – George W. Bush probably won the presidency in his debates against Al Gore. He could win it again – or lose it – in a rapid-fire series of three 90-minute debates with John Kerry starting Thursday night in Miami.

The first debate will focus on national security – Bush’s political strength – with as many as 50 million Americans expected to watch and the race still close enough to shift either way.

If Bush reinforces his standing on the key issue of security, he could solidify or extend the slight lead he enjoys in several recent polls. However, if Kerry convinces voters he has the better plan and steadier hands to safeguard the country, he could pull ahead.

The second debate, in St. Louis on Oct. 8, will allow voters to ask each man questions in a town-hall setting. The third and final debate, on Oct. 13 in Tempe, Ariz., will focus on economic and domestic issues.

The debates will be televised on most networks starting at 9 p.m., as will a debate between vice presidential candidates Dick Cheney and John Edwards on Oct. 5. The debates are sponsored by the bipartisan Commission on Presidential Debates under rules negotiated by the two campaigns. No other candidates had enough support – 15 percent as demonstrated in polls – to be included under commission rules.

“We’re now in prime time,” said Kerry adviser Mike McCurry. “People are beginning to tune in.”

Indeed, Bush and Kerry approach the debates mindful that they represent the last major chance to dramatically change the contours of the long campaign.

Four years ago, Bush entered the debates eight percentage points behind Gore. When they were finished, Bush had an 11-point lead. Though he lost ground over subsequent weeks and eventually lost the popular vote, he’d built enough of a lead to win the Electoral College and the White House.

More than 9 out of 10 voters have made up their minds this year, so that makes that kind of large swing unlikely, unless either candidate does so poorly that he turns off his supporters. Also, some voters in 26 states will have started voting before either man speaks Thursday evening, thanks to early voting or absentee ballots.

Still, the 270 minutes of presidential debates – coincidentally the number of Electoral College votes needed to win the election – will offer undecided voters their best chance to see the two major-party candidates side by side and compare them on style and substance.

On substantive issues of foreign policy and national security, the most critical questions facing each man are: What would you do to keep the country safe from terrorists, how would you secure Iraq, and why should voters trust you to achieve these goals?

Yet style will count as much as substance, and it could both reinforce each man’s arguments and answer lingering questions about their characters and personalities.

Kerry, for example, will criticize the Iraq war as a deepening quagmire in hopes of undermining Bush’s stature as a trustworthy commander in chief. Bush will stick to simple, declarative sentences that help to reinforce his image as clear and decisive.

Bill Clinton is one who understands the political power in such a stance; more than a year ago he observed that Americans would prefer a wartime leader who’s strong and wrong than one who’s weak and right. Of course, Bush backers believe he’s strong and right, but the point is that his stylistic presentation could attract even those who think his policy choice is wrong.

“Bush needs to keep that image constant, that he is going to protect the country and doesn’t care about the consequences,” said Thomas Steinfatt, a professor of communications at the University of Miami, which will host the first debate. “It’s less important for him to be really on top of things as long as he doesn’t make a serious mistake.”

Kerry will strive to keep his remarks short and simple, lest his tendency toward long meandering answers feed an image as waffling or aloof.

Though Kerry has made periodic progress at tightening his speaking style, he slipped back into his familiar pattern Tuesday when visiting a junior high school in Spring Green, Wis. When a 13-year-old girl asked how he would help families pay for college tuitions, Kerry’s answer took six minutes.

Voters attuned to thoughtful policy discussion might favor that, but television tends to reward image over content.

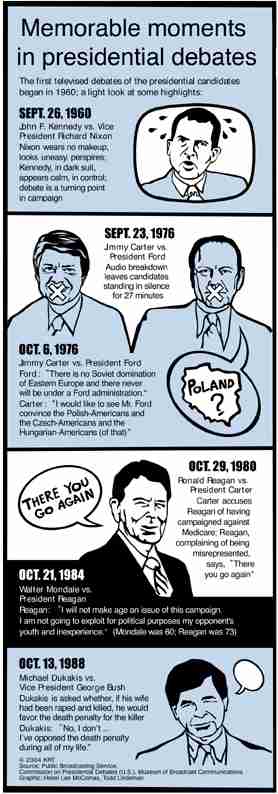

“This could be like 1960 between John Kennedy and Richard Nixon,” said independent pollster John Zogby. “Kerry could win the debate on radio, but lose it on TV.” In 1960, voters who listened to the debate on the radio said they thought Nixon did better, but voters who watched the youthful, handsome Kennedy on television declared him the winner.

Both Bush and Kerry bring long experiences in the format of the modern political debate – a misnomer, since the sessions are really more simultaneous, side-by-side news conferences than debates. The rules prohibit each candidate from directly questioning the other, for example.

“John Kerry is a master of substance,” said former Massachusetts Gov. William Weld, who debated Kerry eight times in his 1996 effort to capture Kerry’s Senate seat. “He is not at all wooden in debate – he is like Br’er Rabbit in the briar patch. He goes regularly for the jugular. He is very, very quick.”

Weld recalled a key moment when he thought he scored a major point against Kerry for the Democrat’s opposition to the death penalty. Weld named the mother of a policeman killed on duty and asked how her son’s life could be worth less than the killer’s.

“I know something about killing,” Kerry shot back, in an obvious reference to his Vietnam combat experience. He said the killer was “scum” who should be locked up forever and that the state didn’t honor life by sanctioning executions.

“Kerry is a master of the fine art of changing the subject,” Weld said. “By the time he finished, everyone had forgotten what the question was.”

Weld said it wasn’t until he watched tapes of the debates later that he realized “just how well-prepared Kerry was.”

Preparation is also a plus for Bush, who surprised many observers with his performance against Texas Gov. Ann Richards, a former college debater, in their one 1994 encounter.

“He was articulate, he made no major mistakes, and he stuck to a few points and hammered them over and over,” said Mary Beth Rogers, who was Richards’ campaign chairwoman. “He still does that today.”