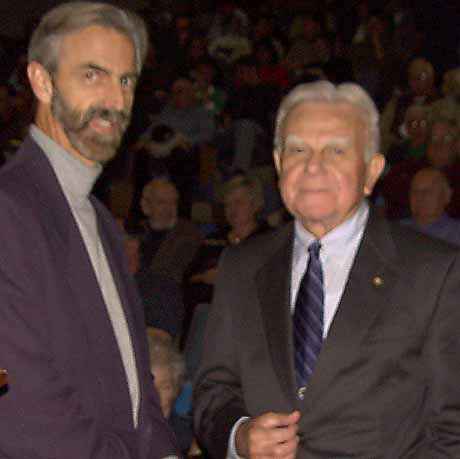

Brittany Contois

Brittany ContoisAmbassador John E. Dulibois, former interrogator at the Nuremberg Trials and author of “Pattern of Circles – An Ambassador’s Story,” gave a riveting account of his interactions with top Nazi officials to a crowd of veterans, students, faculty and other community members.

Dulibois spoke at NKU as part of the Military History Lecture held Oct. 23.

“I’m not a professional lecturer, I’m a storyteller,” Dulibois said.

His story began with an explanation of how he was chosen to be an interrogator of Nazi officials such as Hermann Goering, chief of the Luftwaffe, and Julius Streicher, the “Jew-baiter.”

A native of Luxembourg, Dulibois was born in 1918 and came to America with his father in 1931. He recalled waking up on the boat as they approached America and hearing, what he thought were gunshots. The first thing he saw was the Statue of Liberty and then realized what he was hearing were fireworks. They had arrived on the Fourth of July.

“It was downhill from there. We moved to Akron,” Dulibois said. The crowd roared with laughter – as they did much of the evening.

Although Dulibois was 13, his school in Akron placed him in Kindergarten because he didn’t speak English.

“I was the biggest boy in class,” he said. “Nobody picked on me.”

He expressed his thanks to the school for starting him at the bottom, making him learn the language and allowing him to work his way up.

Dulibois joined the military after graduating with honors from Miami University and working briefly at Procter and Gamble Co.

He recalled a military officer asking what he could do. He told the officer he could speak German and would like to be in military intelligence.

“‘Can you drive a truck’,” the officer responded. “‘No, but I can speak German,'” Dulibois said.

In his humorous way, Dulibois said, “after eighteen months of driving a truck, the army found out I could speak German” and told him he was going to Luxembourg.

“I kept my mouth shut. If I said I wanted to go to Luxembourg, I’d have been sent to the Philippines. That’s how the army works,” he said.

Dulibois was one of five interrogators assigned by the Nazi War Crimes Commission to conduct a pre-trial investigation at the Central Continental Prisoner of War Enclosure #32 in Luxembourg.

At the time, the United States and its allies knew little about the Nazi organization. The interrogators’ job was to find out as much as they could about the organization and the responsibilities of the top-ranking Nazi officials in preparation for the International War Crimes Trials in Nuremberg.

“We had to find answers before we could know what to do,” Dulibois said.

The interrogators were to do briefs on 22 of the highest ranking prisoners of the 86 there.

According to Dulibois, the 22 men segregated themselves into three distinct groups: the German general staff members, the Nazi’s and the bureaucrats.

The German general staff members were the highest-ranking officers among the prisoners. This group included Wilhelm Keitel, chief of staff of the German High Command; Alfred Jodl, chief of operations of the German High Command; Hermann Goering, chief of Luftwaffe (Air Force), among others. They wanted nothing to do with the Nazis.

The Nazis were the criminal element, the trash, according to Dulibois. This group included Julius Streicher, the “Jew-baiter”; Fritz Sauckel, chief of Slave Labor Recruitment; and Hans Frank, responsible for the execution of Jews in Poland. These were the men who stuck by Hitler’s side and Hitler rewarded them by giving them positions to decide life and death. They were the worst of the worst, according to Dulibois.

The bureaucrats were the opportunists, Dulibois said. These men changed political affiliation as political power changed hands just to keep their jobs.

“They wouldn’t talk to each other but they would talk about each other,” Dulibois said. “That was good for the interrogators.”

Guantanomo Bay, used today by the United States to hold al Qaeda members, serves the same purpose as Nuremberg, according to Dulibois. A big difference is that the Germans were divided within the group and were all out to save themselves, Dulibois said. In Guantanomo Bay, the military doesn’t have the same leverage since al Qaeda does not fear the death penalty, he said.

When they first arrived in Nuremberg, Dulibois recalled how surprised he and the other interrogators were by how different all of the German men were from their expectations.

They expected to see all tall, blonde, blue-eyed men. Instead, the first person they saw was Hermann Goering who was about 5’10” tall (and wide), according to Dulibois.

“We stood there with our mouths open,” Dulibois said.

Goering was upset by the surroundings, Dulibois said. He had expected luxury but, instead, got a drab room, guards and a 10-foot fence all around. The fences weren’t around Nuremberg so much to keep the prisoners in, but to keep vigilantes out, according to Dulibois.

Goering asked Dulibois if he was there to ensure the prisoners were treated properly and, “in a moment of insight, I said ‘yes’,” Dulibois said. That is how he got the cover of Welfare Officer.

Dulibois said he was always grateful for that exchange because the prisoners thought of him as a kind of social worker, so he was privy to more information than the other four interrogators. He translated letters and got lots of gossip from the men, which helped the investigation.

Dulibois said Hermann Goering had a great personality and sense of humor. He collected jokes, even jokes about himself, and loved them. He was hard not to like and he had to keep reminding himself that Goering was a top-ranking Nazi, Dulibois said.

Besides a sense of humor, Goering also had a drug addiction. He suffered from addiction the entire time he was in power and, at Nuremberg, took 20 pills in the morning and 20 pills at night, according to Dulibois.

Considering Goering was the number-two man, “that tells something about the Nazis,” he said.

While Dulibois grudgingly admitted to harboring some positive feelings regarding Goering, Julius Streicher, the “Jew-baiter,” was another story. Streicher was editor of Der Sturmer, an anti-Semitic publication, and was known for spreading his hatred of Jews. “He was a unique person in that he was a total failure at everything he did and he blamed all his failings on the Jews,” Dulibois said.

Although Streicher had the lowest IQ of all 22 men, he was an expert on Jewish history, knew the Bible cover-to-cover and had a personal library housing a collection of Jewish manuscripts and documents from all over Europe.

Dulibois found it ironic that the man who was instrumental in advocating the annihilation of the Jewish race, was the very man responsible for preserving their history through his collection.

Eleven men were sentenced to hang, but only 10 actually did. Dulibois recalls Goering telling anyone who would listen that they would never hang him. Dulibois recalled thinking to himself, “hey fat stuff, if anyone hangs, it will be you.”

Goering was sentenced to hang, but he didn’t. He committed suicide one hour before his hanging by biting on a cyanide capsule hidden in a hollow tooth.

Of the remaining 22 men, 18 received prison terms and three were acquitted. Dulibois said he was somewhat disappointed with the outcome of the trials.

There were some who played very important roles, but got only prison terms, Dulibois said.

“The ones that were hanged, fine, there just were not enough of them,” he said.

Dulibois