An artist works on their painting. Mixing colors on a palette, they carefully refine the details and brushstrokes, lovingly rendering the form with their own two hands.

Only to burn it in the end.

The painter takes a blowtorch to the canvas; hours of work begin to burn in a mesmerizing, unpredictable pattern. The small flame devours the material, slowly licking at the edges. The image curls, browns and blackens, falling apart. Holes start to peek through the painting. Faces and bodies melt and contort into abstraction.

For Hez Sumner, this is the most satisfying part.

“When you go through childhood trauma, there are a lot of missing chunks,” Sumner said. “This motif is that physical manifestation of gaps in my memory.”

Sumner is a Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) student, pursuing integrative studies with a concentration in painting, photography and drawing.

The BFA program in the School of the Arts (SOTA) culminates in a capstone project: a senior exhibition that showcases each student’s unique body of work.

BFA exhibitions are displayed at the end of every semester. This year, 13 students have their artwork up in SOTA’s galleries. Like many other BFA students, Sumner began working on their show several semesters ago. They had their concept formed by sophomore year.

“The base concept was childhood memories and trauma, which then led into exploring the raw and intimate, lasting effects of childhood trauma and how neglect, abandonment—all those negative aspects of my childhood—have shaped my identity and the way that I perceive the world,” Sumner said.

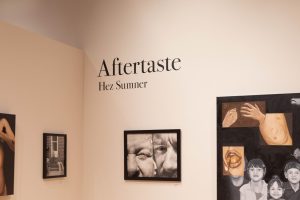

Consisting of nine artworks—a mix of paintings and photographs—the pieces are all monochrome. Some are black and white, while others are sepia-toned browns and yellows. To Sumner, the sepia is meant to convey a sense of sickliness: a lack of color to show a lack of life.

Their exhibit, titled “Aftertaste,” is unified not only by color but also by shared burn marks. After finishing a painting or photograph, Sumner burns their work in chosen places. This unnerving element contributes to the overall vulnerability of the exhibit. Having an unstable upbringing, they turned to art to heal and highlight the stark differences between people’s lives.

“I’m not making typical self-portraits or landscapes,” Sumner said. “I’m investigating and exploring a topic that is really hard to talk about, and it’s uneasy, and a lot of people don’t want to see it. It’s also something that needs to be expressed, because vulnerability is important, especially in art,” Sumner said.

One painting shows a face up close. Fingers violently pry the mouth open, revealing rotted and browning teeth. This is meant to reflect the lack of dental care in Sumner’s family, which has left them with cavities and other dental problems.

In another painting, a hand clutches a stiff body. One arm lifts, revealing skin stretched tightly across visible ribs. This piece comments on Sumner’s history with eating disorders and body dysmorphia, which stems from guilt around money in their family.

“My paintings are more of this experiment with myself and how to portray the lasting physical effects of what’s happened to me,” Sumner said. “I can experiment with that and play with that, play with the brush strokes, play with the colors.”

To work on their shows, BFA students are each assigned a studio space on the fourth floor of SOTA. Covered in errant paint splotches and scattered art supplies, it’s a messy, vibrant collaboration of artists. Across from Sumner is Olive Pfalz’s studio.

The muted yellows and browns of Sumner’s space contrast with Pfalz’s vivid pinks and neon greens. One invites you in its own quiet way; the other demands your attention through its intensity.

Pfalz, another integrative studies BFA student, centers their show on queer identity and trans visibility through painting, sculpture and ceramics. Unlike Sumner, Pfalz was initially unsure what to base their show on. They aspired to make horror art, but pivoted. As an activist, they instead chose to comment on the country’s current political climate.

“I realized that sometimes the scariest things…are the lived experiences of those around you,” Pfalz said. “So I followed that passion. My artwork is really just about whatever I’m most angry about in that moment.”

Pfalz sports neon green hair and is decked out in pink clothing; these complementary colors have become part of their signature style. The colors also appear in their show, as pink is associated with trans identity.

One painting shows Pfalz in a locker room, clutching a towel to their shivering body as a frightened expression plays across their face. This was inspired by a memory from seventh grade, when girls told Pfalz that they couldn’t change with them after a swim meet. That experience—and the feelings that came with it—have stuck with Pfalz ever since.

“Little gay Olive felt like they were gonna explode. I felt like I was put into an ice bath. So I went into the corner of this huge girls’ locker room to change by myself,” Pfalz said.

As a transgender individual, Pfalz comments on the trans experiences in familiar settings such as school or sports. They believe art that displays strong emotions, such as sadness or fear, effectively elicits a response from the viewer.

“There’s this idea that trans people are the perpetrators of violence in sports, when more often than not, they are the victims of violence,” Pfalz said.

In another painting, Pfalz recreates a passport, altering its color to pink—an allusion to the 2025 executive order that restricts gender markers to one’s sex assigned at birth. For Pfalz and other nonbinary individuals, the policy is deeply upsetting. In the artwork, the “F” on the passport is outlined in bright white, while Pfalz’s own face replaces the photo—red-eyed and drenched in water.

The title of their show is “You Give Birth to More of Us Each Day.” This line is a direct quote from Elissa Rae Shupe, the first person legally recognized as nonbinary in the United States. Shupe committed suicide in January, just after the executive order passed, using that line in their final note. Pfalz takes immense inspiration from Shupe, integrating aspects of the trans experience into their show to educate as well as affirm.

“I have two audiences that I’m going for. For people who are queer and trans, I want a sense of community and a sense of ‘I see you,’” Pfalz said. “I want my work to be, at least for people outside of the queer community, a space for educating. I want them to get a sense of sympathy and a sense of understanding.”

In the BFA program, students work closely with professors in their respective fields. Throughout the process, professors conduct check-ins to see the progress. Sumner and Pfalz, both in painting, worked with Kevin Muente, SOTA’s painting professor.

“I had to be there to sometimes say, ‘I don’t think this is going to work,’ or ‘Try something different,’ and try to push them and motivate them and inspire them,” Muente said.

Seeing his students’ final exhibitions is deeply rewarding. Muente, alongside his colleagues, has the expansive role of teaching, supporting and challenging their BFA students.

“Both Hez’s show and Olive’s show are really inspiring to me because they both are making artwork that comes from a place of extreme vulnerability and honesty,” Muente said.

Both artists express vulnerability through their work, particularly by creating art about their past. Addressing such sensitive topics presented them with a set of challenges. For Hez, it felt like re-traumatizing or reliving those experiences. For Pfalz, the weight of the subject left them feeling at times sad, powerless and angry.

However, the shared studio spaces provided a sense of support. Being in an artistic bubble spurred the growth of friendship and creativity.

“If I ever get bored or I just want to look at something that isn’t my work, I have basically a mini gallery around me at all given times,” Pfalz said. “It’s way better than working in a vacuum where you’re all alone.”

The exhibitions are open until May 2. For Sumner, Pfalz and their peers, these shows are more than a graduation requirement—they’re acts of resistance, healing and education. Their art, whether burned by flame or bold in color, is meant to spark something in those who view it. But in confronting what has scorched them, these artists get to reclaim themselves.

“Artistic success is more about this concept of being happy with what you create and not really focusing on what other people want you to create,” Sumner said.