Former police commander shows cracks in his own armor

From police commander to mental health advocate, Chris Prochut has taken steps to stop the stigma surrounding mental illness through sharing his own story.

September 29, 2016

Looking up from his buttoned shirt to wipe his tears, Chris Prochut recalled watching his children, Ashland and Chase, open up Christmas presents and thinking ‘no one is that happy…there is no happiness like that in the world.’

Prochut, a mental health advocate and suicide prevention trainer, took a stand to end the stigma surrounding mental illness. Along with fighting his own mental illness, Prochut has spent the last six years traveling nationwide sharing his journey to survival in hopes to ‘start the conversation about mental health in America.’

“There is no shame asking for help,” Prochut said. “There is only shame missing out on life.”

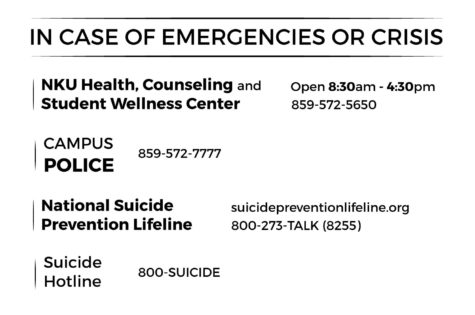

Prochut gave a presentation to the NKU police department and students on Sept. 26 to educate the community on how to seek help and respond to warning signs of suicide.

Signs to look for include: isolation, behavioral changes, feeling hopeless or having no reason to live, talking about being a burden to others, increasing the use of alcohol or drugs, sleeping too little or too much and displaying extreme mood swings.

Prochut, a former Bolingbrook, Illinois police commander, and his career were forever changed on Oct. 28, 2007 by the on-going secrets of his partner, Drew Peterson, and the unraveling murders of his wives.

“I remember the day Stacey Peterson (his fourth wife) went missing,” Prochut said. “I was the officer on press information that day. I knew the news stations were going to call our department until they could get information. No one believed me when I said we needed to get ready because we had an image to protect. I had no other choice but to take it all on my shoulders.

“This was my other family.”

Prochut stayed up countless nights from stress trying to protect his department’s name. Between making lists of what to do, who to call, and how to get the press away, he slowly started to lose himself in the mix of it all.

“I would be instantly ticked off at the world when I wasn’t doing something about the problem at work,” Prochut said. “I inadvertently put the blame on my family every night for my anger and wasn’t pleasant to be around. I started to make myself blind to my own problem.”

Prochut shared the first time family members started to notice and act on his facade. He admited feeling embarrassed to own his weaknesses.

Chris Prochut, a former police chief, has traveled across America sharing his own story. He hopes to help end the stigma surrounding mental illness.

“That’s the first night my armor cracked,” Prochut said. “My sister asked me ‘when are you ever going to be happy again?’ and I knew I was failing at hiding my own problems. I am a cop, a man, and a dad … I can’t show weakness when in reality on the inside I was dying. I am the one who is supposed to help them, they can’t help me.”

Dr. Ben Anderson, director of health counseling and student wellness, was Prochut’s first counselor to try and turn his path around. Anderson said one has to focus on the reality of things instead of avoiding it. He mentioned this being the first time he had seen a case like this in his career.

“He was showing both signs of bipolar disorder and depression,” Anderson said. “This can be a very confusing state and ultimately very lethal for someone. When Chris came in he was a wreck. His life was in shambles from stress and he was at his breaking point. I knew this is when I needed to create doubt in his mind … I needed to derail him off his tracks.”

After trying numerous treatments, Prochut flushed his medication and canceled appointments thinking he was ‘back to his old self.’ That Monday he set his death date for May 1, 2008 as he emptied his desk.

“I had everyone fooled,” Prochut said. “You don’t know how empowering it was to fool people. I may have not had control of myself but I did have control over what they believed about me. I had looked at past cases and records to teach myself the easiest way to do this and the more I thought about it the more I wanted it to be over.”

Later that evening Prochut woke up to four fellow officers in SWAT gear at his bedside. His wife, Jenny, and the children snuck out of the house and down to the station for immediate help from people Prochut would trust and hopefully listen to. If Prochut would have caught her leaving he wouldn’t have been alive by the time she was back.

“My wife saved my life,” Prochut said. “She saw the bedroom light turn on upstairs but knew if she didn’t leave in that moment, not only would she not have me as a husband but she wouldn’t have me at all.”

In the state of Illinois, any officer diagnosed with a mental illness or put on medication for mental illness will have their license removed. Resigning from his career forever and taking the biggest step in his journey, Prochut agreed to spend 15 days under professional watch and medical care to save his own life.

“It was time,” Prochut said. “It was really hard for me to agree to be hospitalized. I didn’t want to give up my image of a man who had it all together. I finally stopped fighting and just did it and later was placed in a 12 by 12 room that I used to be the one fighting people into and cuffing to a gurney.

“That’s where I ended up.”

Looking down at his folded hands and taking a deep breath, Prochut slowly stumbled around the words ‘I finally made it.’

“I remember the day I came home,” Prochut said. “My family has completely reframed my life. When I asked my son what I should do about my job he immediately said ‘be a corndog seller. You don’t need to be superman dad, we just want you here. That right there is the point. You don’t have to be perfect.’”

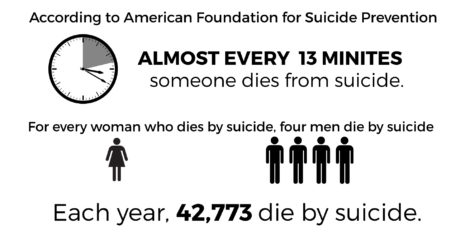

Siobhan Ryan-Perry, alcohol & other drug clinician at the Health, Counseling and Student Wellness Center and peer educator adviser, said suicide is the second cause of death on campuses and a leading factor within law enforcement. By having this event, first responders and students were able to bond with Prochut.

“Having Chris was important to us,” Ryan-Perry said. “Everyone needs a chance to talk and we wanted to create a safe place where the community felt they could do so. We need to also educate everyone to respond to these situations with a serious manner.”

Senior psychology major, Hannah Moore, opened up for the first time in her life after hearing Prochut’s story.

“I admitted for the first time out loud that I have a mental illness to others outside of my inner circle,” Moore said. “This was an emotional and relieving moment at the same time.”

According to Ryan-Perry, the number of students coming through the Health, Counseling and Student Wellness Center is increasingly growing.

“Students come in here with major crisis,” Ryan-Perry said. “Anything that disrupts your daily activity is a crisis. We see a variety of issues but more and more students are reaching out to us. We want students to know our doors are always open to listen without judgment. With the numbers growing that doesn’t mean mental illness is, it means people are talking.”

Prochut said opening up to others with a personal story and experience can be one way to make others feel not alone.

“We need to let everyone know the support that’s out there,” Prochut said. “I think to change the words that we use. Just because this is an illness doesn’t mean it isn’t manageable. People just want relief from the pain they are suffering from but we need to give it in a positive way. People feel shameful and never speak up and it’s the silence that is causing the most damage.”

CORRECTION: A former version of this story inaccurately stated Siobhan Ryan-Perry said suicide is the number one cause of death on campuses. The story has been correctly to accurately reflect that she said suicide is the second cause of death on campuses. The Northerner regrets this mistake.