Against the smog: NKU science students, faculty reflect on proposed federal budget cuts

April 18, 2017

Faced with potential federal cuts to science-based programs and institutions, Dr. Christine Curran spent her spring break walking the halls of Capitol Hill.

She joined other members of the Federation of American Societies of Experimental Biology to fight the proposal, which would affect federally-funded organizations such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Institute of Health (NIH).

The Trump administration has proposed in their budget to cut EPA funding by 31 percent and NIH funding by 18 percent. Scaling back on enforced regulations from the EPA have also been proposed.

An NKU professor primarily in environmental toxicology, as well as physiology and anatomy, Curran admitted that there are definitely concerns relating to these proposals.

“There’s a lot of strong support. Senator Mitch McConnell is strongly supportive of the need of biomedical research funding,” Curran said. “He may have a certain opinion on coal, but he understands that scientific research is important and that it’s good to have an educated workforce.”

Curran said that voters won’t stand for funding cuts and deregulations. If they go too far, there will be pushback. She also added that despite political affiliation, the majority of citizens want healthy kids and a healthy workplace.

“We heard from a lot of people that we would’ve thought ‘Oh, there’s no way. We’re doomed.’ I didn’t leave Washington feeling that way. I felt that it’s going to be an interesting year resolving the 2017 budget that was never approved and the fiscal 2018 budget,” Curran said. “I don’t believe everything is going to evaporate in the same way we saw with healthcare, ‘Absolutely we’re getting rid of it.’ Well, it didn’t happen.

“We’re hearing this very strong statement about the EPA and environmental regulations and funding and we’re not going to go back to ground zero.”

When you could see the smog

On the first Earth Day in 1970, Curran was in eighth grade. Back then, she recalled that they didn’t have the clean air and water act. A lot had recently been cleared near her school for the use of a trash dump.

The Clean Air Act was signed by President Richard Nixon in 1970, which authorized the EPA to establish National Ambient Air Quality Standards meant to protect public health and regulate emissions of air pollutants, according to the EPA. Similar to the CAA, the Clean Water Act came to fruition in 1972 by Nixon, largely amended from the 1948 Federal Water Pollution Control Act.

Together, with her classmates, Curran said they raised money to plant trees. The celebration became parallel to themes within “The Lorax,” the popular Dr. Seuss book.

“One of the things I discovered in environmental toxicology is that people don’t have a good understanding of what happened just a few decades ago,” Curran said. “So, we’re really good about the American Revolution and Civil War, but things that happened in the ‘60s and ‘70s we don’t actually have a good memory of.”

Curran has participated in Earth Day since the start, which is always April 22. Awareness of environmental issues is cyclical, she said. Now, a stuffed Lorax sits on her desk as a reminder of the history.

“It was easier back then because, literally, you went outside and the skies were brown and dirty. What we didn’t realize is that the first things we tried made the skies look a lot nicer, but it also made the particles much smaller,” Curran said. “They traveled further, not only in the environment but in our bodies. So these ultra fine particles can get deep into the lungs and be transferred.”

Adam O’Brien, double major in environmental science and biology, had similar memories.

He currently works as an undergrad research student for Dr. Richard Durtsche. O’Brien said that he can remember seeing the beginnings of all the changes due to the regulations made back in the 70s.

“I remember being in Cincinnati when the smog was so bad that you couldn’t even see the skyline in the summer. Now you can. Even on a bad day, you can still see it,” O’Brien said. “So, it worries me that the changes that are being made are going to undo the last forty years of work. Given how our population has increased and our use of fossil fuels have increased, I feel like we are going to revert back to where we were pre-clean air act and water act.”

‘Maybe our generation isn’t the one’

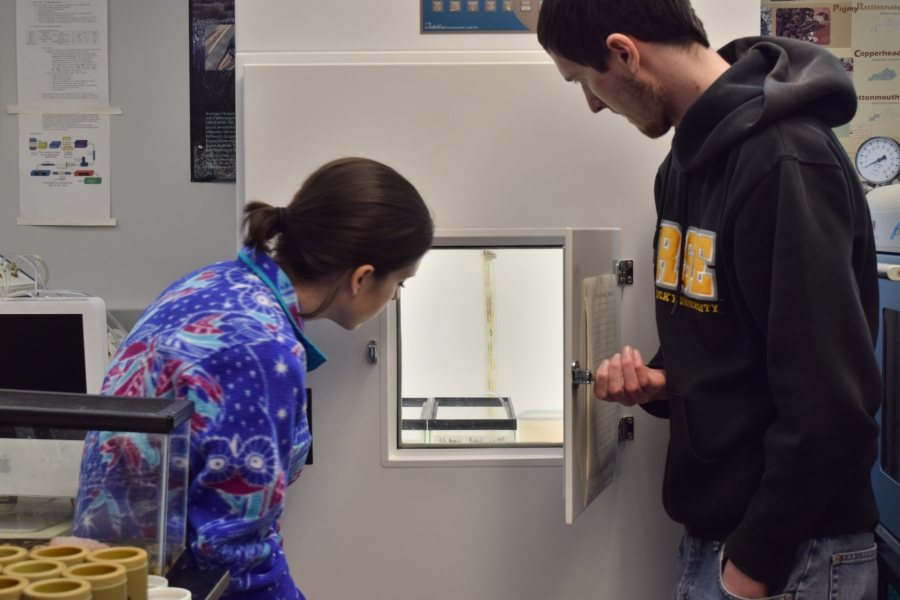

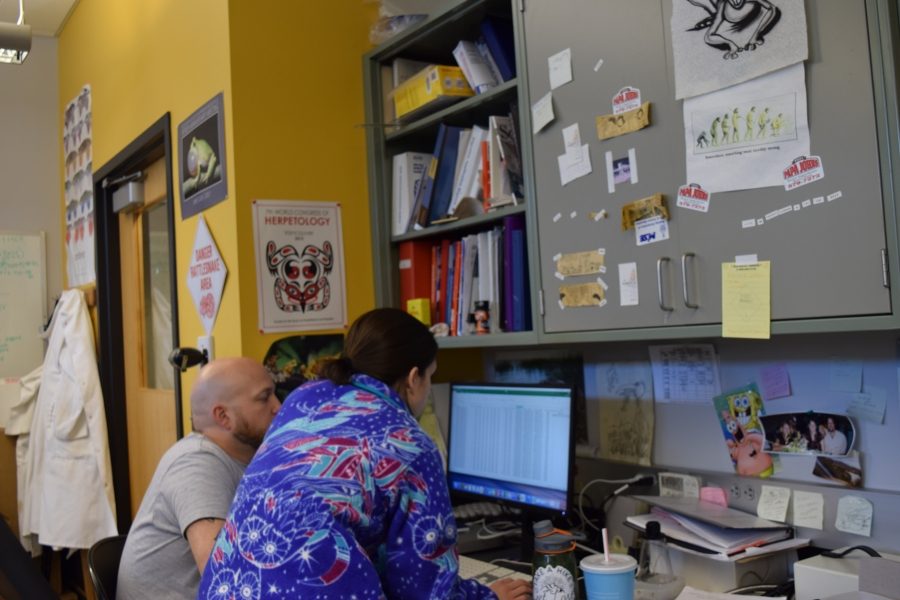

O’Brien works along with a few other students in Dr. Durtsche’s lab, including Valerie Rice. Rice is also a double major in environmental science and biology. They work both on-campus and in the new NKU Research and Education Field station, which is adjacent to the St. Anne Wetlands in Melbourne, KY.

Rice is planning to go into animal conservation work and wildlife rehab. O’Brien wants to work in field research. Both have concerns about the prospects of how cuts and deregulations will affect the science community

The station, on the exterior, is simplistic. Flowers are planted on the walkway to the house, which is backdropped by a wooded area. A myriad of species from birds to frogs to salamanders can be heard.

Working in the field is a more holistic way of learning, according to O’Brien. Their research focuses on the breeding phenologies of frogs, which consists of what time of day they’re calling and for how long, as well as what kind of species appear.

“What we’re looking at is if there’s a difference between the areas they use based on invasive plants; we have those drift fences and pitfall traps set up in different areas,” Rice said. “We have closed and open canopies and within those, we have invasive and non-invasive. So we’re looking at if a species prefers one type over the other or if none of them are using one kind.”

After trapping the species — which consists of everything from frogs to turtles to salamanders–they take them back to the lab. They release the species 24 to 48 hours after their capture.

Generally, there’s less diversity where invasive species are located.

In terms of research opportunities and the future career field in relation to proposed cuts, O’Brien said that it won’t only affect the current generation, but the future one as well, adding that they may not learn to foster an appreciation for science, ecology and climate work.

Recently, he was talking with students in similar majors as himself about the possible changes. They were trying to maintain a sense of hopefulness. Even if things are changing, he said it won’t change what the facts consist of.

“We keep working and studying and doing research regardless of what the powers say because they come and go,” O’Brien said. “Maybe our generation isn’t the one that is able to really make a lot of headway but maybe we do groundbreaking research that gives the next generation the tools they need to fix it when the opportunity comes around for them.”

O’Brien and Rice collect data to further understand populations within the wetlands. Generally, there is less species diversity where invasive species are located.

Rice said it’s frustrating to know about issues relating to climate change and fossil fuels, as well as what the implications of cutting back regulations would implicate.

“I just spent four years learning something,” Rice said, adding that if she couldn’t get the job she wants then she could be a park ranger. “Now everything is being cut. It’s kind of ‘Well, I don’t know what to do.’”

On proposed deregulations, budget cuts

Curran said that in terms of environmental regulation, she teaches her students the difference between risk assessment and risk management.

As a scientist, she did her postdoctoral research at the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health. There, she looked at what would be the recommended level of pollutants that one would be exposed to in the workplace.

That data was given to the regulators, who were allowed to look at what was practical and affordable. Essentially, she said it added reality.

“Risk management adds other aspects, so what you end up with is a level that we thought was safe and it always is raised to a level that we would believe is safe,” Curran said. “What I’m worried about now is that we already know this isn’t safe, and they want to take that away.”

As a professor, she said she tries to give her students a balanced view between the scientists and the regulators.

“It concerns me right now, where we’re headed because we’re literally throwing all the science out the door along with the regulations and that’s never a good place to be,” Curran said.

Dr. Michael Guy, an assistant professor in biochemistry and chemistry is going to the March For Science in Washington D.C., which takes place on Earth Day, April 22. Another march is taking place in Cincinnati.

He said that he currently has eight undergraduate students in his research lab where they’re studying tRNAs, or transfer RNA, which are molecules important for making proteins. Chemical groups are put on the tRNAs by the cell; the research focuses on finding what happens when these groups aren’t put on, and what enzymes assist in this process.

With new enzymes, they can find correlations for diseases. The main reason Guy is going to the March for Science is because of the proposed cuts to NIH, which funds the bulk of his research.

“I’m just going to have a simple sign that says ‘Please don’t cut NIH funding.’ There’s a host of reasons, but really it seems like America has always been a great place to do science,” Guy said. “People from all over the world come here to do science. I feel like if we start cutting that off we’re going to lose that edge.”

While Guy will be going with a simplistic approach for his poster at the march, he says his high school daughter is planning something “epic”.

Guy worked as a postdoctoral fellow before he came to NKU as a professor. Much of his research has been tied to NIH, which had a budget of roughly $32 billion in 2016.

According to NIH, more than 80 percent of their budget is given through 50,000 grants to more than 300,000 researchers. 10 percent of their budget supports research and projects within their own campus, located in Bethesda, Maryland.

Guy said that one of the best aspects of coming to NKU for students is the ability to do undergrad research; it makes them more attractive to employers and gives them tangible experience.

Guy added that he’s applying for a federal grant from NIH. About 17 percent of people who apply receive this.

“If you do a 20 percent cut on that, it’s down to something like 13 percent of people get funded,” Guy said. “Maybe directly [students] don’t understand or know exactly what it’s going to do, but I think they’re worried that the future generation of students won’t be able to do undergraduate research.”

While EPA does not directly fund research, Curran said that countless students have benefitted from having been involved as interns or on EPA-related projects, such as People, Prosperit, and the Planet, or P3.

P3 is a college competition channeled through the EPA for designing sustainable solutions. In 2015, the EPA funded NKU $15,000 for the transdisciplinary project, which was an app that allowed users to see their carbon footprint as well as ways to reduce it.

Curran added that there’s an EPA lab in Clifton, Ohio and they often have scientists from those labs come in for lectures. They also often work with testing levels of pharmaceuticals and other waste that show up in nearby waterways.

The line between advocacy and science

Despite planning to attend the March for Science, Guy said that if scientists do go march, there’s a worry that people will equate them with politics.

As scientists, he says they teach to follow data wherever it leads, despite political beliefs.

“The president has put forth this budget and it’s been nice to see that both Republicans and Democrats have said, ‘Wait a second. Funding for science is important,’ Guy said “I guess the worry is that if scientists go out and march, Republicans would see that as ‘Oh, they’re against Republicans.’”

Curran said that, despite political beliefs, she teaches her students to guide themselves through the scientific method to come to their own conclusions. In science, she said, one doesn’t prove anything; they have data that supports. When others start cherry-picking data and misleading the public, it becomes an issues. In the classroom, she said that’s an educator not an advocator.

Guy recently went to a conference where there were multiple talks on how scientists are viewed by the public. In general, he believes scientists are respected and seen as fair.

“Politically, I voted for Republicans and Democrats. I consider myself a moderate independent,” Guy said. “This is enough to get a moderate independent to go to D.C. It’s pretty extraordinary to have this situation happen.”

Cailey Radcliffe is a sophomore environmental science student. They have gone to multiple demonstrations, including the Dakota Access Pipeline protest.

“It was really empowering. There were some veterans there and I remember, one said to me–I thanked him for being there–and he said ‘I love you, sweetheart,’” Radcliffe said. “Everyone was really supportive there. Everyone was giving one another signs. It was just like a big family.”

Radcliffe has attended several demonstrations and protests, including the #NODAPL. They said that they considered themselves an activist.

When they learned that the administration decided to move forward with the oil pipeline Radcliffe felt hurt by the action. Though it was expected, they added that the pain was still felt.

In terms of cutting funding and regulations, Radcliffe said that it could restrict what people do job-wise and cut careers already in place.

“We definitely need those regulations in place so we’re drinking clean water, breathing clean air and not taking harmful toxins into our bodies constantly like you see in overpopulated places like China that have smog covering everything and people have high asthma rates and different diseases that affect your respiratory system,” Radcliffe said. “Depending on which regulations are taken back will determine which systems in our bodies will be affected.”

Guy said part of the pushback for regulating and funding these agencies and organizations may come from citizens not knowing what they’re getting out of it.

He used the example of the ‘war on cancer,’ referring to the 1971 National Cancer Act signed by Richard Nixon. The act increased efforts to find cures for cancer. He said that one of the criticisms is that a lot of money was funneled into the cause, but it didn’t necessarily cure cancer.

“Well, it’s a legitimate concern. You, know ‘What are we getting out of this? We’re not getting all these cures.’ To that I’d say, ‘We are getting cures. It’s not as fast as we’d like sometimes, but in addition to that we’re training the next generation of scientists,’” Guy said. “We’re providing a livelihood for 400,000 people.”

Radcliffe said that most people don’t realize how much of a disconnect there is between humans and nature.

“I grew up around nature. All my life I’ve spent it looking at people through a nature lens. I see the disconnect between people and where their food comes from. It comes from farmers, but they see it as coming from supermarkets,” Radcliffe said. “There’s a disconnect there. There’s a disconnect in what keeps our air clean and how it affects human health.”

Radcliffe interned for the Sierra Club, whose mission statement is to “explore, enjoy and protect the planet.” The organization also promotes responsible use of earth’s resources. Here, Radcliffe helped organize volunteer and looking up legal permits to counteract a mine in Anderson Township, Martin Marietta.

The connection between nature and humans is something that O’Brien said younger generations seem to be more aware of.

Valerie Rice and Adam O’Brien with their professor, Dr. Richard Durtsche. They conduct undergrad research at the new Research and Education Field Station, located by the St. Anne Wetlands.

“Hopefully in the next 10 years or so things will start to move in a different direction as everyone who is coming out of college in the next 10 years finishes undergrad, finishes grad school and gets into professional careers and policy-making careers,” O’Brien said.

He said that there’s a lot of safeguards and guidelines in how scientists conduct research. Even if the presentation seems skewed, the data and numbers themselves are factual.

“Numbers don’t lie. They can’t lie. People lie,” O’Brien said.