From addiction to advocacy

NKU student uses personal experiences to shatter the stigma of addiction

October 5, 2015

From the back seat of his father’s car, Jason Merrick went into violent convulsions. Between losing and regaining consciousness, his face was burning and his skin was coated in beads of sweat. He screamed profanities at his little brother between episodes of vomiting. For the first time in his life, the 30-year-old was experiencing withdrawals.

It had been several years since Merrick had seen his father. He had traveled across the country half a dozen times by the time he was in his 20s, running from consequence and desperate to sustain a living. His father and stepmom now had a son; he was 5-years-old and Merrick had never met him.

In an effort to reunite his family, Merrick’s father drove from California to Columbus to pick him up and bring him home.

Jason Merrick is a graduate student at NKU. He will graduate in May with a Master’s Degree in social work.

The now 44-year-old Northern Kentucky University student recalls what was supposed to be a cross-country journey with his family as one of the most excruciating moments of his life.

Trees whizzed past the windows as Merrick was struck senseless with the symptoms of withdrawal. Unable to use in the vehicle, the only way the sickness would subside was when he was able to drink liquor at gas station stops along the way.

Decades of bad choices brought Merrick to this painful moment.

“At 12-years-old, I was making those decisions, I decided to use, I decided to try to be like the grown ups, and smoke the pot and drink the alcohol, and use the drugs,” Merrick said. “Somewhere very soon after that, there was a moment in time where it stopped being a choice, and started becoming a necessity.

“In order for me to function, in order for me to go to school, in order for me to study, in order for me to be an employee, in order for me to wake up and for me to sleep at night I had to have some kind of substance in my body because my body wasn’t able to function normally without it, and by definition, that’s a disease,” Merrick said. “The scariest part is you don’t know where that is, you don’t know where that line is in the sand and you cross it, and now you’re physically addicted.”

Merrick’s disease followed him all the way to Northern California, where he continued living the only way he knew how. With little responsibilities other than his girlfriend at the time, he began growing marijuana on a 10-acre plot of land.

He and his girlfriend had a home together with her two daughters. She was not aware of the extent of his sickness. In the clutches of addiction, it was normal for Merrick to be pulled out of his sleep, shaking from withdrawal. He would take a shot of whiskey in the middle of the night to stop the shakes. His addiction became so frightening for his girlfriend and her children that they had to leave their home.

Completely delusional, Merrick left his home and isolated himself in the woods. With nothing but a 20-gauge shotgun by his side, he lived in a treehouse overlooking his garden. He stayed there for months, drinking and using crystal meth daily. He was sick from drug-induced malnutrition and sleep deprivation. He spent his days hearing helicopters whip through the wind. He was terrified of the lizard-like creatures that he saw crawling in the trees.

“Society condemns people who are suffering from this disease,” Merrick said. “I thought I was lucky to be able to hide up there and die and be abandoned up there. I was ready. I was done. It was time for me. It was over for me. I had dug my grave. Everybody says it’s a choice, everybody says I’m a piece of shit because of what I’ve done, so just let me die up on this hill and I’ll be a happy man.”

Desperate for help, he reached out to his girlfriend. He expected her to escort him off of the property and send him to jail. At the very least, he felt like he deserved to be abandoned for what he had done to her family.

But she did not abandon him.

The very next day she stood at the bottom of his tree stand.

She was not with a sheriff.

She was not angry.

Instead she shouted, “Jason, come down from there and get the help you deserve.”

“She came up there, and she said to me that I deserved help, and that there was help available,” Merrick said. “With that kind of empathy, and that kind of understanding, that’s the only thing that really broke down that barrier for me to come down and get help.”

Merrick enrolled in a rehab facility for 28 days. But the stay was not enough to alter the composition of his brain. He relapsed shortly after he was released.

With nothing left in California, he packed up the only thing he had, 15 pounds of marijuana, and hit the road.

He drove around the country with his product, selling marijuana and blowing money in a never ending cycle. From Portland to Houston to Salt Lake City, Merrick’s only companions were a bottle of whiskey in the passenger seat and a crack pipe in the ash tray.

As his product and money began to dwindle, not only was he sick with addiction, but now he was starving.

He woke abruptly one morning with the pavement as his pillow. He was lying in the middle of a busy downtown street. He had come out of a blackout.

He had no idea where he was.

Nor did he know what day it was.

With his cheek pressed to the concrete he could make out people in business suits. A concerned passerby hovered over him, his cell phone at his ear.

Merrick could no longer deny that he needed help. He had an aunt who lived in Northern Kentucky. She took him in on one condition- that he received treatment.

He began attending AA meetings, where he heard about The Grateful Life Center, a residential recovery service in Erlanger.

The next day he was at their front door asking for a bed.

He was accepted into the program, and for the first time in years, Jason Merrick had a home.

“That’s where I really got a solid foundation of recovery… I met all these beautiful people that were dedicating their lives and their careers to helping people like me,” Merrick said. “I found a connection to a power greater than myself, who I choose to call God. This network of sobriety meetings and of people in this area in unlike anywhere else I’ve ever seen.”

Through his recovery, he met Sandy Bollhauer, the program coordinator at the time. Bollhauer said that her first impression of Merrick was that he was very serious about the program. She said he complied with all of the rules and never caused any problems.

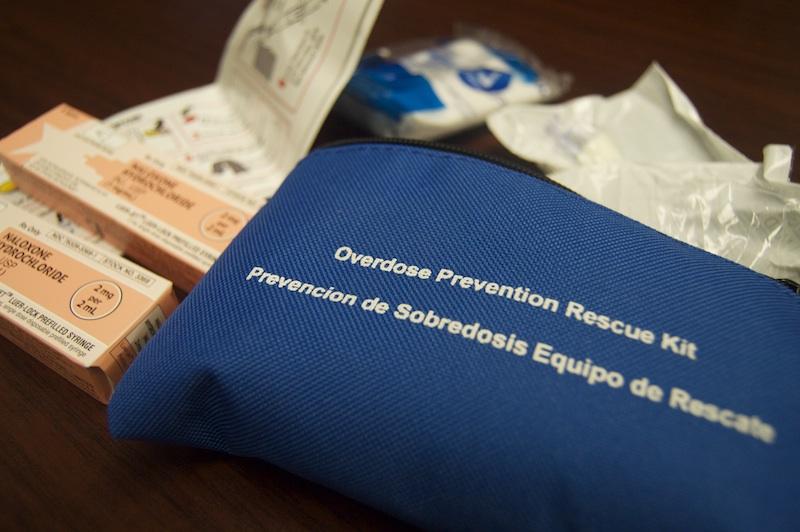

Jason Merrick demonstrates the use of overdose kits in his office at the Kenton County Detention Center.

She remembers him being very quiet, so she was taken by surprise when he approached her one day to talk.

He asked her what he could do to be of service and to help others like himself.

Bollhauer stressed that he focused on his recovery. She advised him to complete the program and to get enrolled in school.

“I did exactly that,” Merrick said. “I finished the program, I enrolled at NKU, and I got a job at that place, at The Grateful Life Center. I started working there the day after I left, 13 months and 1 day, and I started working there.”

He began studying social work at NKU. For the next five years, he attended class during the week, and he worked at The Grateful Life Center on the weekends.

While taking Social Work 405: Community Organizations, Merrick was inspired to help his region battle its epidemic with heroin addiction.

He helped develop a grassroots community organization, Northern Kentucky People Advocating Recovery, a program dedicated to break down barriers between addiction and recovery.

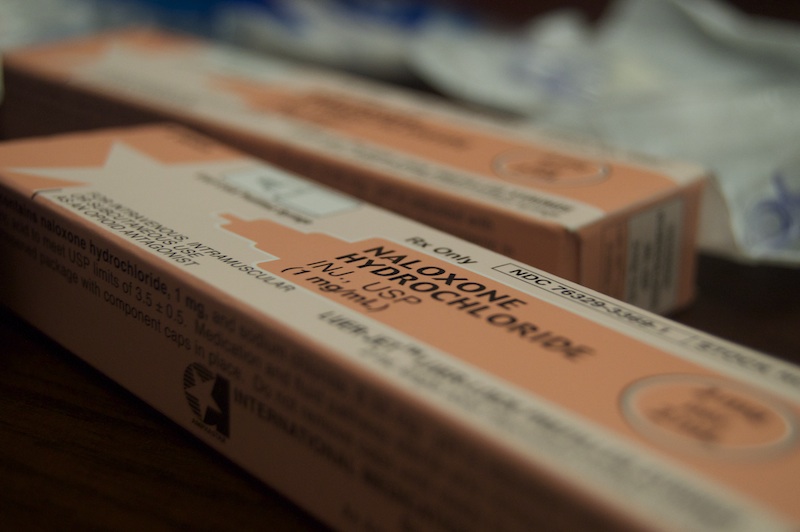

Overdose prevention kits contain two doses of Naloxone, an opioid antagonist that restores respiration in the event of an overdose.

Through NKY PAR, a committee was created to promote House Bill 366. This bill allows the public prescription and distribution of Naloxone, an opioid antagonist, providing ordinary people with the tools to prevent heroin overdose deaths.

When administered to someone who has overdosed, Naloxone, also known as Narcan, temporarily reverses the effects of a potentially fatal overdose.

Dr. Perilou Goddard, a psychology professor who specializes in addiction studies, has her own overdose kit that she received by completing training through NKY PAR.

She explained that although heroin is neither a stimulant or depressant, it has a predominantly depressant effect.

She said that heroin suppresses respiration, and too much of the opioid drug will stop breathing altogether.

“[Naloxone] is a very benign drug,” Goddard said. “It rapidly restores breathing, and triggers immediate withdrawal. What it does is it kicks the heroin out of those receptors in the brain, and replaces them with Naloxone.”

Goddard said that the drug is available as an injection or an intranasal spray. It has no adverse effects and it cannot be abused.

There is controversy surrounding the use of Naloxone, as some argue that the drug will only encourage the use of heroin.

“The only thing that Naloxone enables is breathing,” Goddard said. “And you may say, ‘Well that person may go right back to using heroin,’ and that’s true. But you can’t stop using if you’re dead. While the person is alive, there is still hope that the person may recover from heroin addiction.”

Merrick helped develop an overdose prevention and response protocol program through NKY PAR. He teaches members of the community how to identify someone who has overdosed, and how to administer Naloxone in the form of an intranasal spray.

Those who complete the training class receive their own overdose prevention kit.

Each overdose prevention kit includes two doses of Naloxone, step-by-step instructions, a nasal atomizer delivery device, a rescue breathing mask, latex gloves and a list of local treatment facilities.

“Advocacy work is what PAR is all about,” Merrick said. “The mission statement is to eliminate barriers to recovery from addiction, so whatever that means. Mostly it’s about education and participation and legislation, giving people the opportunity to volunteer to be a part of the solution.”

Merrick said that NKY PAR has been to every legislative session involving heroin since the organization was founded in 2012.

“We actually sit down with our lawmakers and help them to write these bills that better serve the people that are suffering, their families and for law enforcement,” Merrick said. “We want to remove the predatory dealers from the streets.”

Kristie Blanchet, a board member of PAR, met Merrick through social work classes at NKU. She has worked with him to conduct Naloxone training classes, and to equip law enforcement officials with stick resistant gloves and sharps containers.

“That is to protect them from accidental needle sticks, but also to help them when they get those phone calls from the community to pick up the syringes that are left lying around,” Blanchet said. “We educate them on hepatitis, HIV, and how to properly dispose of needles.”

Blanchet said that Merrick’s passion for outreach in the community is evident in his work through NKY PAR.

“He was in the throes of addiction, and he really found a home here in Northern Kentucky, and the community took him in,” Blanchet said. “Now he’s fighting to get help for people in this area. He’s fighting nationally, but also fighting for Northern Kentucky because it’s in his backyard. This is the community that took him in, and cared for him, and really helped him achieve what he can do today.”

Since working with Blanchet through NKY PAR, Merrick has also helped to develop a program in the Kenton County Detention Center teaching drug prevention classes to inmates.

Since July he has been managing the full-time program, overseeing 70 men and 30 women, all while enrolled in graduate school at NKU.

“They have classes in the morning, classes in the afternoon, and meetings in the evenings,” Merrick said. “It’s an all day thing, five days a week, and they do their own meetings on the weekends.”

Blanchet said that Merrick’s program in the detention center is a program that the community has been lacking. The program has provided inmates with the tools necessary to recover from addiction.

“Nobody deserves to die from this,” Blanchet said. “It’s really sad, the state that our society is in today in regards to addiction, and recovery, and the views on it. He works very, very hard to reduce the stigma of this disease. He lives his life reducing the stigma of addiction and recovery.”

Resources